| |

By Fr. Ronald G. Roberson, CSP

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

by Michael J.L. La Civita

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

Celebrating with the Hutsuls of the Carpathian Mountains

text by Matthew Matuszak and Petro Didula

photographs by Petro Didula

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

Slovakia’s Greek Catholic Heritage

by Jacqueline Ruyak with photographs by Andrej Bán & Jacqueline Ruyak

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

Around Slovakia

Compiled by, Zuzana Vilikovská

Reprinted here with Permission of

The Slovak Spectator

by, Stephanie MacLellan

Reprinted here with Permission of

The Slovak Spectator

The Carpatho-Rusyns of Austria-Hungary

by, Thomas A. Peters, C.G.R.S.

"The Slovak Spectator", Robin Rigg

End of the millennial struggle

by, Brian J Pozun, 7 May 2001

Passaic, New Jersey - 1890 to 1930

by, Joy E. Kovalycsik

by Yelena Simrenko

by, Mr. Vladimir Bohinc

Despite the fact that the Ruthenians are the fourth largest ethnic group in Slovakia, few people are familiar with their culture

by, Andrea Chalupa

Special to the Spectator

Passaic, New Jersey - 1890 to 1930

by, Joy E. Kovalycsik

Carpatho-Rusyns and the Vojvodina

by, Brian J Pozun, 26 June 2000

Rusyns in Central and Eastern Europe

by, Brian J Pozun, 7 May 2001

Reprinted here with Permission of

The Slovak Spectator

Minority Heritages of Slovakia

by, Joseph Levin

by, Matthew J. Reynolds - Spectator Staff

Reprinted here with Permission of

The Slovak Spectator

by, Julianna Chickov

by, Julianna Chickov

by, Maria Boysak

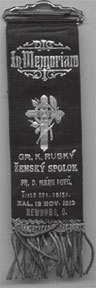

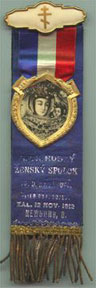

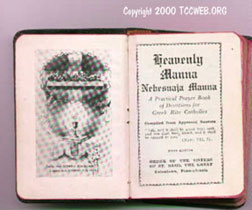

Sample Images

Radio Free Europe

Prague, Czech Republic

by, Matthew J. Reynolds - Spectator Staff

Reprinted here with Permission of

The Slovak Spectator

The Lemko are finding the reconstruction of their ethnic identity hindered by a variety of internal divisions.

by, Karen M Laun, 5 December 1999

Emphasizing Procedures & Pitfalls

Lecture Handout - 1996

by, Thomas A. Peters

Certified Genealogical Records Specialist

8 August 2002

Posted with Permission of...

BBC News Online

The Slovak Catholic Church

By Fr. Ronald G. Roberson, CSP

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

The religious history of Greek Catholics in Slovakia is closely related to that of the Ruthenians. Indeed, for centuries their histories were intertwined, since the 1646 Union of Užhorod was almost unanimously accepted in the territory that is now eastern Slovakia.

At the end of World War I, most Greek Catholic Ruthenians and Slovaks were included within the territory of the new Czechoslovak republic, including the dioceses of Prešov and Mukačevo. During the interwar period a significant movement back towards Orthodoxy took place among these Greek Catholics. In 1937 the Byzantine diocese of Prešov, which had been created on September 22, 1818, was removed from the jurisdiction of the Hungarian primate and made immediately subject to the Holy See.

At the end of World War II, Transcarpathia with the diocese of Mukačevo was annexed by the Soviet Union. The diocese of Prešov then included all the Greek Catholics that remained in Czechoslovakia.

In April 1950, soon after the communist takeover of Czechoslovakia, a mock “synod” was convoked at Prešov at which five priests and a number of laymen signed a document declaring that the union with Rome was dissolved and asking to be received into the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate (the Orthodox Church of Czechoslovakia after 1951). Bishop Gojdic of Prešov and his auxiliary, Bishop Basil Hopko, were imprisoned. Bishop Gojdic died in prison from harsh treatment in 1960; Bishop Hopko was released from prison in 1968 and died in 1976.

This situation persisted until 1968 when, under the influence of the “Prague Spring” presided over by Alexander Dubcek, former Greek Catholic parishes were allowed to return to Catholicism if they so desired. Of 292 parishes involved, 205 voted to return to communion with Rome. This was one of the few Dubcek reforms that survived the Soviet invasion of 1968. Most of their church buildings, however, remained in the hands of the Orthodox. Under the new non-communist Slovak government, most of these had been returned to the Slovak Greek Catholic Church by 1993. In 1997 Pope John Paul II created an Apostolic Exarchate of Kosice, Slovakia, from territory taken from the Prešov diocese. The Pope also beatified Bishop Gojdic in 2001 and Bishop Hopko in 2003.

A Greek Catholic Theological College was founded in Prešov in 1880. It was handed over to the Orthodox in 1950. In 1990, after the fall of communism, the Greek Catholic theological school was revived and incorporated into the Pavol Jozef Safarik University of Kosice. On January 1, 1997, a Slovak government decree established a new University of Prešov and mandated that the theological school in Kosice be transferred there. Since 2005 it has been known as the Greek Catholic Faculty of Theology of the University of Prešov. Its specific task is to provide for the scientific and theological formation of candidates for priesthood and those who are preparing to serve in various other ministries.

The Prešov diocese includes a considerable number of ethnic Rusyn Greek Catholics. In recent times, however, they have been absorbed into Slovak culture to a certain extent, as very few religious books are available in Rusyn, and the liturgy is almost always celebrated in either Church Slavonic or Slovak. In the 2001 Slovak census, 24,000 people claimed Rusyn ethnicity.

By 2006 the two jurisdictions in Slovakia had about 218,000 faithful and 256 parishes served by 386 diocesan and 34 religious priests. There were 131 women religious, and 92 seminarians. In the United States and most other areas, the Slovaks are not distinguished from the Ruthenians. They have a separate diocese, however, in Canada, at present presided over by Bishop John Pažak (Eparchy of Sts. Cyril and Methodius of Toronto, 223 Carlton Road, Unionville, Ontario L3R 2L8). There are seven parishes and six priests for about 25,000 Slovak Greek Catholics in Canada.

On January 30, 2008, Pope Benedict XVI reorganized the Greek CatholicChurch in Slovakia and raised it to the status of a Metropolitan Churchsui iuris. In doing so, he elevated the eparchy of Presov toMetropolitan See, elevated the Apostolic Exarchate of Kosice to thestatus of eparchy, and created a new eparchy in Bratislava, the Slovak capital.

by Michael J.L. La Civita

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

Yugoslavia, the “land of the Southern Slavs,” was the fruit of an intellectual concept born in Europe in the 19th century. Members of the intelligentsia speculated that a union of the Balkans’ Southern Slavs — Catholic Croats and Slovenes, Muslim Bosniaks and Orthodox Macedonians, Montenegrins and Serbs — would free them from the yoke of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, which had competed for control of the Balkan Peninsula for centuries. Yugoslavia, the “land of the Southern Slavs,” was the fruit of an intellectual concept born in Europe in the 19th century. Members of the intelligentsia speculated that a union of the Balkans’ Southern Slavs — Catholic Croats and Slovenes, Muslim Bosniaks and Orthodox Macedonians, Montenegrins and Serbs — would free them from the yoke of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, which had competed for control of the Balkan Peninsula for centuries.

In December 1918, after the collapse of the two empires, an uneasy union of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was achieved, and the king of Serbia was proclaimed its head. Until its dismemberment in 1991, the Yugoslav experiment proved defective, as rival groups jostled one another for supremacy.

Despite the Yugoslav collapse, its former constituents turned on one another in a bloodletting that did not abate until the new millennium. Bosniaks, Croats, Kosovar Albanians and Serbs were all complicit in mass murder, ethnic cleansing, rape and other acts of wanton violence. Today, an eerie calm presides over the Balkans — “the powder keg of Europe.”

Lost in the confusion were Yugoslav minorities — Greek Catholics, Jews and Protestants. The 58,000 Greek Catholics of Yugoslavia were particularly vulnerable; perceived by both Croat and Serb extremists as neither Catholic nor Byzantine, they included six distinct groups: Orthodox Serbs who accepted papal authority; Croats from the village of Žumberak; Rusyns who left the Carpathians in the 18th century; Macedonians who accepted papal authority; Ukrainians who left Galicia at the turn of the 20th century; and Romanians living in the Serbian province of Vojvodina.

After the Yugoslav kingdom was created in 1918, the Holy See extended the jurisdiction of the Eparchy of Križevci, (erected in 1777) to embrace all Yugoslavian Greek Catholics. Since the disintegration of the Southern Slav state, the Holy See has regrouped them into three separate jurisdictions.

Eparchy of Križevci. Based in the town of Križevci, near the Croatian capital city of Zagreb, the eparchy includes about 21,350 people living in Croatia, Slovenia and Bosnia and Herzegovina and is led by Bishop Nikola Nino Kekić.

When the Ottoman Turks first invaded the Balkans in the 14th century, they smashed states that had squabbled among themselves since the Byzantine hegemony of the peninsula evaporated in the 12th century. The wars between the Ottomans and the powers of Central Europe that followed provoked a significant refugee problem. Tens of thousands of Serbs sought safety in the Military Frontier of the Hapsburg emperors. Bishops and generals, peasants and soldiers brought their icons and weapons, families and retainers. The Hapsburgs guaranteed the Serbs certain privileges, including the freedom to set up eparchies and monasteries.

In the late 16th century, the Serbs established an Orthodox monastery in the village of Stara Marča, near Zagreb, which eventually became the focus of a pro-Catholic party within the Serbian Orthodox community. In 1611, the pope appointed a bishop for them. He served as the Byzantine vicar of the Latin Catholic bishop of Zagreb and established his residence at the monastery.

This spurred controversy. Refusing to acknowledge the authority of the Latin bishop of Zagreb, Serbian monks rallied the Orthodox faithful, who turned the Catholic party out of the monastery, setting it aflame in 1739. In 1775, the monastery was liquidated by the Hapsburgs and two years later the Holy See erected a Greek Catholic eparchy, locating it in the nearby town of Križevci.

Many of the eparchy’s Rusyn Greek Catholics immigrated to the United States in the first two decades of the 20th century, settling in Chicago, Cleveland and Pittsburgh. Some of those who remained eventually left their villages and settled in Zagreb, where many were absorbed into the Latin Catholic majority.

Macedonia. In 2001, the Holy See established an exarchate for Greek Catholics living in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. Led by the Latin bishop of Skopje, Kiro Stojanov, it includes some 15,000 faithful.

Greek Catholics in Macedonia descend largely from families who were received into the Catholic Church in the 19th century, due to the efforts of a Bulgarian priest, Joseph Sokolsky. Ordained to the episcopate by Pope Pius IX in 1861, he was named “archbishop for Bulgarian Catholics of the Byzantine rite.” This newly independent church grew rapidly, and within a decade more than 60,000 Bulgarian Orthodox Christians opted for communion with Rome.

By the end of the century, however, three quarters of those who joined the Greek Catholic community returned to Orthodoxy. Surviving Greek Catholics lived in a few isolated villages in what is now Macedonia.

Serbia and Montenegro. In 2003, the Holy See set up an exarchate for Greek Catholics in Serbia and Montenegro. Led by Bishop Djura Džudžar, it includes about 22,500 members, most of whom are ethnic Rusyns living in the Serbian region of Vojvodina.

Though now divided, the Greek Catholics of the former Yugoslavia share the same liturgical language, Church Slavonic, and the same Byzantine rites associated with the Orthodox churches of Bulgaria, Romania, Russia, Serbia and Ukraine.

Michael La Civita is CNEWA’s assistant secretary for communications.

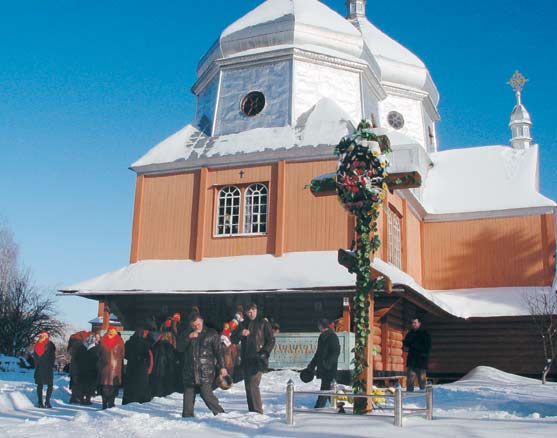

Celebrating with the Hutsuls of the Carpathian Mountains

text by Matthew Matuszak and Petro Didula

photographs by Petro Didula

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

I’ve traveled the world a bit and I have to say no one celebrates holidays quite like the Hutsuls,” says Yurii Prodoniuk, a resident of Kosmach, a village of 6,200.

Tucked into the Carpathian Mountains in southwestern Ukraine, Kosmach is the center of the 500,000-strong Greek Catholic and Orthodox Hutsul community.

The 13th-century Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus – which includes parts of present-day Belarus, Russia and Ukraine – is an essential chapter in Hutsul history. Many of those who survived the ruthless devastation of their homeland, peasants mostly, headed for the hills, seeking refuge in the Carpathians.

The earliest written references identifying these refugees as Hutsuls date to 14th- and early 15th-century Polish documents.

The intensification of serfdom, which bound the peasants to the land, provoked another exodus to the mountains hundreds of years later.

Today, the descendants of these refugees live in an area covering 2,500 square miles in southwestern Ukraine and northern Romania.

“In general, the Hutsuls are conservative,” says Roman Kyrchiv, professor emeritus of philology at the Institute of Ukrainian Studies of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. “It was difficult for them to accept Christianity. They were attached to their pre-Christian traditions.”

Christianity, in its Byzantine form, arrived in Kievan Rus with the baptism of its grand duke, Vladimir, in 988.

“There are remnants of pre-Christian pantheism in some Christmas carols,” Mr. Kyrchiv continues. Instead of referring to the infant Jesus, Mary, Joseph or the Magi, these carols simply recount village life and ask for prosperity for neighbors. To “Christianize” the carols, Hutsuls sometimes add a refrain after every verse, such as “O God, grant.”

For centuries church leaders sought to end the singing of these carols, Mr. Kyrchiv says. Bishop Hryhorii Khomyshyn, the Greek Catholic Bishop of Ivano-Frankivsk in the first half of the 20th century, advised that “Hutsul Christmas carols be rooted out.” But the head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church from 1901 to 1944, Metropolitan Archbishop Andrey Sheptytsky of Lviv, thought otherwise, even writing a pastoral letter to the Hutsuls in their own distinctive dialect, which is similar to literary Ukrainian but with some Romanian influences.

Mykhailo Didushytskyi, a local woodcarver, sits outside his home in Kosmach.

Though for centuries geographically isolated, the Hutsuls were not insulated from the outside world. Depending on who governed the region and when (Catholic Poland and Austria to the west, Orthodox Russia to the east), Hutsuls, while true to their Byzantine Christian faith, were either Greek Catholic or Orthodox. “But this [jurisdictional divide] didn’t mean much to the people,” Mr. Kyrchiv says. Historically, Greek Catholics and Orthodox “celebrated religious feasts in each other’s churches.”

For centuries, Kosmach had but one parish, which was Greek Catholic, until the Soviets suppressed it in March 1946, forcing it to integrate with the Russian Orthodox Church.

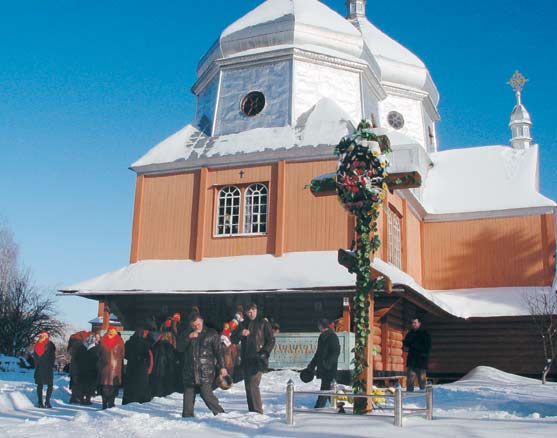

Snow drapes the church during the Christmas Day liturgy.

Though deprived of its church, Kosmach’s Greek Catholic community survived; many celebrated the sacraments in secret while others participated in the Orthodox rite. This state of affairs lasted four decades, until the Soviet Union unraveled, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church resurfaced and Ukraine achieved independence.

Today, mixed Greek Catholic and Orthodox Hutsul communities are the norm. But with proximity comes competition; this surfaces mainly during Theophany, the great feast of Christ’s baptism commemorated 12 days after Christmas. Both communities process to the river for the blessing of water.

“The Orthodox stand at one place for the blessing, but Greek Catholics go farther up the river so the Orthodox drink ‘Catholic’ water,” says longtime resident Mykhailo Didushytskyi. “I laugh and cry. Adults act like children. There’s a contest: The Orthodox want the Catholics to try the water first and vice versa.”

For the Hutsuls, however, tradition remains more important than denomination.

“They don’t listen to the priest,” says Father Vasylii Hunchak, pastor of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox parish of Sts. Peter and Paul in Kosmach.

For example, Father Hunchak instructs his faithful that they can work on minor holy days. “They say, the priest says that, but my mother says we can’t work,’” Father Hunchak continues. “Their beliefs are more important than what Christ handed down.”

“The Hutsuls are convinced this is how they avoid disaster,” Mr. Prodoniuk says. “They celebrate every minor holy day by not working the land. They celebrate not only St. Ann, St. Andrew and St. Nicholas, but St. Barbara and all the feasts of St. John,” he continues. “Misfortune doesn’t touch them. Other regions have floods, storms, earthquakes and other natural disasters. These pass by the Hutsuls.

“On holy days, the women don’t even use a knife,” Mr. Prodoniuk adds. “The day before the feast, they slice a lot of bread. They also make bread out of potatoes and corn, which can be broken by hand.”

The Soviets tried to modernize and socialize the Hutsuls with mixed results. Electricity may have been introduced, but collectivization failed. With a dearth of agricultural land, and with communities scattered throughout the Carpathians, logging and raising cattle and sheep remained the primary means of livelihood.

The Soviets frowned on tradition, particularly those traditions rooted in religion. But the Hutsuls took pride in their distinctive dress, dances and songs, says Vasyl Markus, editor of the Encyclopedia of the Ukrainian Diaspora and a professor at Loyola University in Chicago. Families continued to decorate Easter eggs, or pysanky, as well as practice embroidery and other examples of folk art. And unlike most parts of the Soviet Union, religious expression never really wavered. But that expression is not purely Christian.

“The Christian faith in the area is nuanced,” says Father Hunchak. “There is faith, but it is not exactly Christian, rather half-Christian, half-pagan … a mystical faith. In the Carpathian Mountains, there are people who know about trees, plants, nature.” The Hutsuls are intimately connected to nature, the elements and to their dead.

“Before Christmas Eve supper, people visit cemeteries,” says Mr. Didushytskyi. “They put candles on the graves of their relatives and invite them to come for supper. A place is then left at the table, with plate and utensils for a deceased relative, to show respect for the dead.”

Timing is important.

“When the cattle are fed and the first star appears, we sit down at the table, light candles and pray,” Mr. Didushytskyi continues. “The eldest takes the kuttia [porridge made of wheat, honey, nuts and poppy seeds] and throws it on the ceiling with a spoon.” If the porridge sticks, this means God has blessed the family with health, cattle and fertile fields.

Caroling remains an important Christmas tradition. “According to legend, God gave gifts to all the countries,” says Father Hunchak, “Ukraine came late and God had nothing left to give except songs. Our Christmas carols are simply gifts from God.”

Anna Havryliuk’s grandchildren prepare for a night of caroling.

On Christmas Eve, grandchildren carol for their grandparents. On Christmas Day, older children carol. After that, however, only adult men who have permission from their pastors may carol. Proceeds from the singing – carolers receive “tips” – are donated to the parish.

“In some villages, first they sing to the man and woman of the house, then the cattle and the fields so that all will be healthy, they will have a good harvest and healthy animals,” says Mr. Didushytskyi.

“They can carol for a whole day at one house, if the man of the house provides enough food and drink. In the 1980’s some carolers came to Kosmach from another village to make more money,” he remembers. “At first people didn’t know the difference, but now they don’t give outsiders anything.”

But outside ways are making an impact on the Hutsuls; a dearth of job opportunities threatens the Hutsuls and their traditions.

“There’s no work in the village,” says a native of Kosmach, Anna Havryliuk. “Young people leave the country looking for work in the Czech Republic, Portugal and Italy.”

Still, even as they venture out into the world, the Hutsuls hang on to their traditions. On Christmas visits, Mrs. Havryliuk’s three grandchildren never fail to return to carol.

Slovakia’s Greek Catholic Heritage

by Jacqueline Ruyak with photographs by Andrej Bán & Jacqueline Ruyak

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

Early morning sunshine fills St. Basil the Great Church in Krajné Čierno. (photo: Andrej Bán)

On a cold and wet November day, a group of carpenters hammered away at the roof of St. Michael the Archangel Greek Catholic Church in the village of Ladomirová in northeastern Slovakia. Built in 1742, St. Michael’s stands out as perhaps Slovakia’s most beautiful and celebrated historic wooden church. Surveying the men’s work, the church’s pastor, Father Peter Jakub, explained that after 40 years, it was time to replace the worn hand-cut spruce shingles.

Only some 50 wooden churches, most dating back two centuries, survive in the modern central European republic of Slovakia; historians estimate more than 300 may have been built between the 16th and 18th centuries. Approximately 30 belong to the Slovak Greek Catholic Church. A handful have been closed and restored as museums, while the remaining churches are used by Evangelical Protestant or Latin (Roman) Catholic congregations. In recent decades, the Slovak government has designated 27 of these tserkvi (Slavonic for wooden churches) as national cultural monuments.

These wooden structures are inexorably fragile, vulnerable to decay and fire. But as architectural achievements constructed during a tumultuous and religiously volatile era, they now galvanize significant interest in and support for their restoration and preservation.

The lion’s share of Slovakia’s wooden churches clusters in the eastern region of Prešov, a mountainous and heavily forested area bordering Poland and Ukraine. Rusyn Greek Catholics — who inhabited tiny hamlets scattered throughout the Carpathian Mountains — constructed most of these churches.

A distinct Slavic ethnic group of poor peasant farmers, foresters and shepherds, early Rusyns followed the Byzantine form of the Christian faith even as the churches of East and West parted company after the Great Schism in 1054.

Rooted in the rites and disciplines of the Church of Mukačevo, now a town in Ukraine, Orthodox Rusyns attracted little attention from their predominantly Roman Catholic neighbors, if for no other reason than because of their isolation.

But in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, sociopolitical and religious events — the Protestant Reformation, the Ottoman Turkish invasion of central Europe and the rise of the Hapsburg Dynasty — prompted these Rusyn Orthodox communities to enter into full communion with the Church of Rome. As Greek Catholics, Rusyns maintained their liturgical rites, customs and privileges, including a married clergy, while professing union with the papacy.

A neatly kept cemetery surrounds the closed wooden Church of the Dormition in Hunkovce. (photo: Jacqueline Ruyak)

Gifted loggers and carpenters, Rusyns preferred wood when building sacred and secular structures. Both practical and ornamental, woodwork adorns church towers, gates, doors and beam supports. Hand-forged wooden hinges and locks on hand-carved doors also characterize many of the churches. In place of nails, the Rusyns fashioned square wood pegs to hold together their elaborate wooden edifices.

Pointing to the heavy square pegs that fasten St. Michael’s wood frame, Father Jakub explained that Rusyn custom at the time forbade the use of metal nails in building churches. According to tradition, Jesus had been crucified with iron nails.

An edict issued by Hapsburg Emperor Leopold I in 1681 reinforced Rusyn building preferences. The edict limited construction of stone churches to Roman Catholics alone. It also stipulated that non-Roman Catholics build their sanctuaries outside the village or town center and within a fixed time period, usually one year.

Whereas medieval Gothic, Renaissance or Baroque churches inspire awe, overwhelming the visitor with their splendor, the smaller and simpler Rusyn Greek Catholic tserkvi make one feel at home, welcomed. Usually built atop hills away from bustling village life, these wooden churches inspire a sense of height and transcendence not by their size, but rather by their location.

“The famous Gothic reredos in Levoča is about 70 meters [224 feet] tall. That’s the height of the wooden church in Mikulašová,” said Martin Mešša, former director of the Slovak National Museum in Bratislava, contrasting Roman and Rusyn Greek Catholic churches.

“Gothic churches were built for 5,000 not 500. It’s town versus country,” he added. Though modest, Rusyn Greek Catholic wooden churches still required the expertise of specialized carpenters, sophisticated architectural techniques and significant financial sponsorship for their construction. Parishioners contributed what they could, but more often, major donations from local wealthy landowners finished the work. For instance, Prince Ferenc II Rákóczi (1676-1735), Hungary’s wealthiest landowner and leader of the Hungarian uprising against the Hapsburgs, rewarded his Rusyn Greek Catholic soldiers by financing the construction of many of their churches.

While each of Slovakia’s Greek Catholic wooden churches is unique, most share basic architectural elements. Essentially a polygonal building, a tserkva’s structural design resembles that of a typical log cabin. Interlocking logs provide the structural frame and walls of the church. Generally, the surfaces of the logs of the exterior are left rounded, while interior logs are hand-planed to create a flat surface.

When assembling the frame, the original builders often preferred logs of red spruce for its high content of tannic acid, which acts as a natural preservative. They also used cedar, pine and birch. Wood siding, usually spruce and cedar shingles, covers the frame to preserve it and insulate the church. Until recently, church caretakers treated the exterior with a dark brown stain. Now they use a colorless protective treatment that allows the wood surfaces of many of the churches to acquire their natural patina.

Most of the churches possess three principal and distinct chambers, usually with three corresponding roofs, each of which may be multilayered and hipped.

Each roof usually climaxes in a cupola, tower or onion dome crowned with an iron cross. Small crosses and stars often ornament the iron crosses and may symbolize the Virgin Mary, the Magi or the Passion of Christ. Other motifs include sunlike circles, the Greek letters alpha and omega, and leaves. As with icons, said Mr. Messa, the wooden churches and their ornaments functioned as didactic elements for illiterate Rusyns.

Oriented from east to west, the cupolas or towers descend in height from the west.

“The towers in aggregate symbolize the Trinity,” said Father Jakub, “and light is the coming of Christ.

“The towers are built so the light of the rising sun hits all three at the same time.”

The tallest tower often contains the bells; its corresponding chamber constitutes the church entrance and the babinec, or narthex, a vestibule for penitents and others restricted from the nave. In the past, this included women.

The middle tower or cupola houses the nave, where the faithful worship. Its high ceiling generally has an octagonal form and symbolizes eternity.

The smallest tower rises above the sanctuary, reserved for the priests and ministers of the altar. Traditionally, the sanctuary is slightly higher, a step or two, than the nave and recalls the “step up to the higher world of paradise.”

The iconostasis — a wall of icons — divides the nave from the sanctuary.

Notwithstanding these shared elements, the architectural design of individual wooden churches varies widely, depending on the community’s needs, wealth, available talent and cultural expressions.

Some, for example Sts. Cosmas and Damian in Lukov-Venécia, have open porches. Centuries ago, a single church served several villages. People from neighboring communities would walk to the church the night before the celebration of the Divine Liturgy and camp on the porch.

In many ways, Ladomirová’s church dedicated to the Archangel Michael exemplifies Slovakia’s Rusyn Greek Catholic wooden churches. Built at the edge of the village, a split rail fence topped with shingles runs around the church. The wooden, roofed gate culminates in an onion dome crowned with an iron cross. And among the graves in the churchyard stands an old wooden bell, also shingled.

The church’s Baroque iconostasis, featuring intricate and colorful carvings and icons, shimmers in the church’s cool light.

At its center, an elaborately decorated royal door is flanked by subdued doors reserved for the deacons and other liturgical ministers.

A row of medallions, each containing a cherub with three pairs of wings with which to cover himself in the presence of God, lines the bottom of the screen.

Above the cherubim, large icons of St. Nicholas, the Virgin Mary holding her son, Christ as Pantocrator, or judge, and the eponymous St. Michael the Archangel have been ordered according to ancient tradition.

Above these icons, images from the life of Christ are depicted; the Last Supper is centered above the royal door.

Icons of the Twelve Apostles, with Christ seated as righteous judge in the middle, compose the next row on the screen.

Lastly, a row of medallions, each featuring a prophet — flanking an icon of the crucifixion — runs along the top.

Since the 18th century, most icons and iconostases such as those at St. Michael’s were made in specialized workshops in Prešov, Bardejov and Cracow, then part of the Hapsburg’s Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Šariš Museum in Bardejov boasts a collection of nearly 450 icons from former churches.

In the early 1990’s, when St. Michael’s reopened (the Communists had closed the church), its icons and carved frame were sent to Bratislava for restoration. In 2006, an annual competition among restoration specialists awarded a prize to the craftsmen who lovingly renewed this unique work of liturgical art.

Since 2000, extensive restoration has begun on many of Slovakia’s wooden churches, with experts and craftsmen focusing on precious icons and iconostases and external carvings, frames and shingles. Specialized contractors now undertake most of this restoration work.

About 650 people, including 400 Roma, belong to St. Michael’s. But Father Peter Jakub’s pastoral duties also include celebrating the Divine Liturgy on Sundays and holy days at two neighboring Greek Catholic churches: St. Michael the Archangel in Šemetkovce and St. Basil the Great in Krajné Čierno.

St. Michael’s in Šemetkovce serves the village’s 90 residents, all of whom are Greek Catholic. Built in 1752, the wooden church was moved to its present site — high on a hill overlooking the hamlet — in the 1780’s. Board and batten cover the log structure and polychrome trims the edges. Only the first and tallest tower culminates in an onion dome; the two lower towers have gradated roofs topped with cupolas. Iron crosses, decorated with small crosses at arms’ end, crown all three towers.

The church’s wood-shingled roof is scheduled for cleaning this year. Replaced in 2001, the shingles have already acquired a thick blanket of moss and lichen. Damaged from water leaking through the old roof, a prominent mural inside the sanctuary awaits restoration once funding becomes available.

Inside the church, Father Jakub pointed out the altered icon of St. Thomas on the intricate 18th-century Baroque iconostasis, which had to be cut to fit into place. The church also possesses some rare 17th-century icons, depicting St. Michael and the raising of Lazarus.

St. Basil the Great is one of two churches that serve Krajné Čierno’s tiny population of 65. Built in 1730, St. Basil has three towers that, like its wooden gate, end in conical shingled roofs. Unlike most other wooden churches, the babinec and nave are the same width. Exceptionally small, the sanctuary allowed room for only one deacon door in its elaborately carved iconostasis. Between 1999 and 2004, St. Basil’s was fully restored. Treated with a colorless preservative, its new wood siding exudes a natural sheen.

When he first came to Ladomirová, the priest knew little about wooden churches. He now makes all decisions on restoration for the three churches, writing grant proposals and meeting with officials from the Ministry of Culture, the main source of funding.

Maintaining and restoring these wooden churches require a great amount of money. For example, the cost to restore one icon runs about $5,000. Unfortunately, the Presov region, where most of the country’s wooden churches are located, ranks as Slovakia’s poorest. Whereas Slovakia’s overall average monthly income reaches upward of $900, in the northeast it hovers closer to $350. Neither the parish communities nor the eparchies of the Slovak Greek Catholic Church can fund the restoration work, invaluable as it may be. To assist with expenses, the wooden churches charge visitors an admission fee and sell postcards.

Several important tserkvi survive just north of Ladomirová near Dukla, Poland. During World War II, this quaint countryside witnessed some of the bloodiest fighting on the Eastern Front. Probably Slovakia’s most picturesque wooden church, St. Nicholas in Bodružal, has been nominated — with Ladomirová’s St. Michael the Archangel — as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Nestled in the wooded foothills of the Carpathian Mountains, it sits high on a long slope off the road at the edge of the village. Built in 1658, St. Nicholas has three tiered towers, each with an onion dome and iron cross. A coordinated wood-roofed fence surrounds the tserkva.

The church’s caretaker, Helena Kažmirova, reflexively picked up windblown twigs and branches as she hurried along the path to the church.

An aging bell maker walks toward St. Michael’s bell tower in Ladomirová to assess repairs. (photo: Andrej Bán)

Mrs. Kažmirova assumed her duties three years ago from her late father. Unlocking the door, she pointed out the bells overhead in the church’s first and tallest tower. She and her husband, Peter, also ring the bells for the parish.

Bodruzal once had a population of about 250, but in recent years it has dwindled to 50, of which seven families are Greek Catholic. “Young people go to towns to work,” she said, “and old people die.” Her own children work in Scotland and Ireland.

About 30 houses remain in the village, but most people live elsewhere. The village, Mrs. Kažmirova said, has produced many doctors, teachers and other educated people. Those who work in the region tend to come back on weekends to attend the liturgy and visit the graves of loved ones.

The Divine Liturgy used to be celebrated at St. Nicholas’s every Sunday, even during the Communist regime. “Maybe we were far enough out of the way to get away with it,” Mrs. Kažmirova speculated. But with fewer villagers, St. Nicholas’s now shares one priest with four other churches in the area; the priest rotates Sunday liturgy among the churches and the villagers follow him.

Several years ago, combined local and international funding paid for a new board-and-batten covering on the exterior of the church, which cost some $50,000. A new and much-needed electrical and security system is expected to cost about the same.

Inside St. Nicholas’s, icons glowed in the sunlight. Restored in the 1990’s, the elaborately carved, mid-18th-century iconostasis has only a very narrow deacon door — barely a foot wide — on its right-hand side. The parish community call the custom-made door the “children’s door,” as its use was limited to children alone when assisting in the liturgy.

A blemish on the church’s ceiling marks the spot where a German grenade crashed through during World War II. Miraculously, it fell to the floor but did not explode. The village’s traditional wooden houses, however, were leveled in the fighting.

Near the Polish border, perched on a low cliff on the outskirts of Hraničné, is the Roman Catholic Church of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary. For centuries, Roman and Greek Catholics worshiped there, alternating liturgies from one Sunday to the next.

“But it really wasn’t practical because the holidays were different,” said caretaker Stefan Sdašak.

“Half of the village would be celebrating while the other half was working.”

At its peak, the village had as many as 600 residents. Today, only 220 villagers remain, all of whom are Roman Catholics.

First constructed in 1785, the church was rebuilt in the 19th century and then moved in 1972 when the adjacent road was widened. Exposed logs at the church’s foundation reveal its wooden frame. The church has a single, large tower, covered with wood shingles that climaxes in an onion dome and iron cross. An imposing Baroque pulpit and a trio of altars, dating from 1670, divide the nave from the sanctuary — gifts from a wealthy Roman Catholic parish in the nearby town of Stará L’ubovňa. A handful of icons, vestiges of the Greek Catholic past, hangs inside the church.

Several years ago, the villagers attempted to sell the church to an open-air museum and build a new one of brick. However, as a registered National Cultural Monument, the church cannot be sold easily. Meanwhile, the small village struggles to find the money to maintain the church.

“Upkeep is expensive,” said Mr. Sdašak. “There’s always something needing attention.”

Around Slovakia

Compiled by, Zuzana Vilikovská

Reprinted here with Permission of

The Slovak Spectator

THE CULTURAL and Education Centre (MKaOS) in Snina in eastern Slovakia, together with the Homeland Museum in Humenné, organised the 10th Podvihorlatský Folklore festival over the second weekend of May. The 10th version of the event also reached a milestone since the first festival had been organised 25 years ago to celebrate the various activities of associations representing Slovakia’s Ruthenian citizens.

This year’s programme included a concert of folklore music featuring the Vihorlat ensemble followed by 17 other folklore groups such as Šiňava, Starinčanka, Dúha, Dukát and others. Altogether there were 350 performers – both young and old – who also presented family traditions and rituals in a gala programme called Rodina, rodina, rodinôčka moja (Family, family, my dear family). Folklore and popular music bands and ensembles from Moravia in the Czech Republic also enhanced the festival together with a country band called Fox.

The TASR newswire wrote that a contest for the area’s best traditional pies, tatarčené pirohy, was part of the festival for the first time. Teams of three were asked to make these popular delicacies but they had to produce at least 60 pies that were then judged on appearance and taste. But the crucial thing was not so much to win but instead to have fun and draw attention to this popular local food, TASR wrote. Demonstrations of traditional crafts were also offered around the ponds of Snina.

The festival organisers said the main idea of the event was to show the good relations among various ethnic minorities in eastern Slovakia.

by, Stephanie MacLellan

Reprinted here with Permission of

The Slovak Spectator

One thing you'll notice when you drive into the northeastern part of Slovakia is that road signs suddenly start appearing in Cyrillic script. The language is Ruthenian, or Rusyn - the native tongue of an ethnic group that's not widely known outside of this country.

About 40,000 Slovaks declared themselves to be Rusyn in the last census, but other estimates say there are more than 150,000 in the country. Their dialect draws from Slovak, Polish and Hungarian. Their faith is Greek-Catholic, which blends Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions.

The Rusyns have had a rocky and complicated history. The biggest blow was likely forced migration to Ukraine and mandatory Ukrainian educa-tion following the Second World War. Many more immigrated to the United States, including the parents of Andy Warhol.

The traditional Rusyn area, in the hills south of the Carpathian mountains near the eastern part of the country, has its own distinct architecture and atmosphere. You might have a hard time getting around by bus, but if you have access to a car, it makes a great place for a road trip.

Svidník

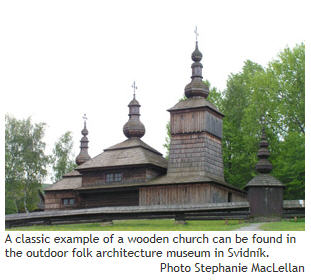

"Remember this, because they won't build anything else like it."

That was a comment someone left in the guest book at the Múzeum ukrajinskej a rusínskej dediny (Ukrainian and Rusyn Village Museum) skanzen in Svidník. Indeed, all of the buildings were constructed centuries ago and brought to the site in 1975, and it's hard to imagine how such a collection could be assembled again. That was a comment someone left in the guest book at the Múzeum ukrajinskej a rusínskej dediny (Ukrainian and Rusyn Village Museum) skanzen in Svidník. Indeed, all of the buildings were constructed centuries ago and brought to the site in 1975, and it's hard to imagine how such a collection could be assembled again.

The museum contains a couple of dozen houses that were built between the late 18th century and the early 20th century. They were brought to the skanzen from the neighbouring Rusyn villages where they were found. The style and building materials vary: some roofs are thatched while others have wooden shingles; some walls are made of wooden beams, some use clay bricks and others are plastered and covered in the traditional sky blue paint. The homes are furnished with simple wooden furniture, with pictures of icons hanging in the corners and decorated ceramics on the walls.

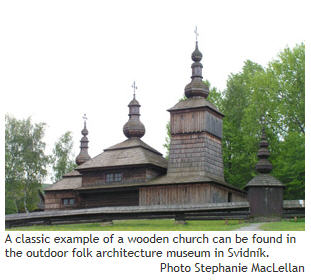

Along with the houses, you can find a school house, fire hall, saw mill and grain mill. The latter has mill equipment that was restored in 1907, including a basket where the corn was fed decorated with painted flowers and carved birds. The wooden church, St. Paraskieva, was constructed in 1766 and contains icons from that era.

The skanzen does re-create the feel of a Rusyn village, especially with goats, sheep and a very friendly donkey wandering around. When you see the paneláky of Svidník from the hilltop site, it reminds you how valuable the buildings really are.

While you're in Svidník, you can learn more about the area's heritage at the Múzeum ukrajinsko-rusínskej kultúry (Museum of Ukrainian-Rusyn Culture). Among the treasures are rare books with intricate handwritten text in Cyrillic, beautifully decorated Easter eggs, traditional costumes and old farm tools and wooden chests. There is also a frighteningly complete collection of mounted animals and birds from the region.

Svidník also has a massive Soviet war memorial and museum, due to its location close to the Dukla Pass. This was a major mountain crossing where 60,000 Soviet soldiers and 6,500 Slovaks and Czechs died in battle during the Second World War, trying to reclaim the pass from the Nazis. Today, near the Polish border crossing at Vyšný Komárnik, there is a memorial at the battle site and an open-air museum of army vehicles and bunkers, which you can see from a watchtower.

Wooden churches

There are dozens of wooden churches - also called "cerkvas" - scattered throughout the northeastern part of Slovakia. They all have three steeples and dark wood exteriors, but beyond that, each church really has its own character. There are dozens of wooden churches - also called "cerkvas" - scattered throughout the northeastern part of Slovakia. They all have three steeples and dark wood exteriors, but beyond that, each church really has its own character.

Some churches are contained in folk architecture skanzens, but it's not quite the same as seeing them in the villages where they were built, where they're sometimes still used by the community. Maps available at different tourist centres can point you in the direction of the churches. Most of them will be closed when you get there, but there will be signs that let you know where to get the key.

It's hard to know where to start with so many churches. My friend and I picked two by planning a route from Bardejov to Kežmarok.

The first church we saw was the Sv. Františka Assiského (St. Francis of Assissi) church at Hervatov, southwest of Bardejov. It's rare because it's a Roman Catholic wooden church. It's not one of the most esthetically-pleasing churches from the outside, with a very boxy, rectangular steeple. But on the inside, it contains some fascinating wall paintings. They include murals of St. George killing the dragon and the Wise and Foolish Virgins parable. The murals were painted by Andrej Haffčik in 1665 and owe their existence to two sets of restoration: the first in 1805, and more recently in 1970. In addition, the altar depicting the Virgin Mary, St. Catherine and St. Barbara dates from 1460 to 1470.

From Hervatov, you drive northwest through some lovely rolling fields and hills before you get to Krivé, where the Sv. Lukáša evanjelistu (St. Luke the Evangelist) church is found. It took a bit of a wait to find someone with the church key - she was working outside and apparently felt very inconvenienced by the interruption.

This Greek Catholic church has a fairly rectangular ground plan, with a steeple that looks like it's been recently added. It's also fairly young, built in 1826, but another church existed on that site previously.

The simple outward appearance belies an interior rich with icons. The iconostasis behind the altar takes up most of the front wall with a cacophony of different saints and prophets. There are two Royal Doors, one from the early 18th century and another from the 17th century. Other icons date from the 16th century. According to the church's information, "Similar artistic features can be found on icons on the Polish side of the Carpathian mountains. One can assume, then, that they were made in one of the workshops in Poland."

The village of Krivé still uses the church for its weekly masses, and according to the woman who gave us the key, it's always full.

The Carpatho-Rusyns of Austria-Hungary

by, Thomas A. Peters, C.G.R.S.The Carpathian Connection would like to thank Mr. Thomas A. Peters, for offering this essay. He has extensive knowledge of the Carpatho-Rusyn people and is a guest speaker on this subject. Mr. Peters also performs professional genealogy services regarding this heritage and the regions they inhabited.

INTRODUCTION

Have you ever been asked the question: "What is your ethnic background?" Most of us, I am sure, have been asked this question many times, particularly be fellow genealogists. We all have the ready answers: "I’m German; I’m Irish; I’m English;" ad infinitum. Yet, there are about one million descendants of an ethnically distinct people from the Carpathian Mountains region of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire who have a confused or non-existent sense of ethnic identity. These descendants of late 19th and early 20th century immigrants know that they are of Slavic ancestry but are unsure to which specific ethnic group they belong to. This is understandable when you examine the origins of the Carpatho-Rusyns. They came from a specific geographic area with defined ethno-linguistic boundaries in the northeast region of Austria-Hungary.

This area encompassed the western part of Galicia and the old Hungarian counties of Saros; Zemplen; Szepes; Abauj; Ung; Ugocsa; Bereg and Maramaros. This area is now occupied by the countries of Poland; Slovakia; Ukraine; Hungary and a few villages in Romania. These immigrants originated in a small area of a very large empire. They did not come from a specific country. Furthermore, they were members of the Greek (Byzantine) Catholic Church (also called Uniate) and the Russian Orthodox Church, both of which were totally unfamiliar to native born Americans. Their clergy were not required to be celibate. It was indeed a difficult thing for Americans to comprehend. Even the Roman Catholic bishops in the United States, in some cases, refused to believe that Catholic priests could be married! As you might imagine, this caused many an unpleasant incident when Eastern Rite Catholic priests came to America and presented themselves to the local Roman Catholic bishop as per the custom. In some cases, communications between the two sides were strained to the point that Roman Catholic bishops refused to grant faculties to the Greek Catholic priests. These priests often were insulted and angry because they were refused permission to exercise their religious rituals which were allowed by the Holy See and many converted to Orthodoxy along with their congregation. This "conversion" required no change in their religious rituals.

Confusion extended to the secular life as well and it was no small wonder then that the Rusyns did not know how to respond to their American friends and neighbors to the question: "What is your ethnic identity?" Some of the immigrants responded that they were Austrian or Hungarian because they came from Austro-Hungarian Empire. Some said that they were Ukrainian (these were few in number). These persons of Ukrainian national orientation came primarily from the eastern reaches of Galicia, the area east of the San River, where ethnic Ukrainians were numerous and very nationalistic. This Ukrainian identification was reinforced by Metropolitan Syl’vester Sembratovyc. Some countered that they were Russian because they were members of the Russian Orthodox church. The Orthodox priests reinforced this identity. This was a very confusing situation to say the least!

The immigrants within their own ethnic community called themselves: Rusyn; Rusnak; Ruthene; Ruthenian; Carpatho-Russian; Carpatho-Ruthenian; Carpatho-Ukranian and Lemko. These terms have a religious connotation signifying membership in either the Greek Catholic or Russian Orthodox Church. Some of the immigrants and their offspring called themselves "Slavish" which is a slang term meaning "like Slovak but not quite!" The Rusyns have a phrase in their own Rusyn language in which they refer to themselves as the "Po-nasomu" People. This in effect meant to them: people who look like us and speak like us. These words were often used in response to the question: "Who are you?" Such an answer leads one to the conclusion that a nationalistic identity problem did exist and still does, for this East Slavic group of people.

SUMMARY:

WHAT IS A CARPATHO-RUSYN?

-

A Distinctive Ethnic Group Who Live Near the Crests of the Carpathian Mountains in Central Europe.

-

Greek Catholic or Orthodox Church Members

-

Speak an East Slavic Language: Rusyn

"The Slovak Spectator", Robin RiggReprinted here with Permission ofThe Slovak Spectator

Ruthenians have lived in the easternmost part of Slovakia and westernmost part of Ukraine - called Sub-Carpathian Russia - since the 14th century. Their dialect is related to Ukrainian, but still maintains its own distinct flair. Ruthenians are a real ethnic group, no matter how hard other nationalities have tried to assimilate them. In the 1991 Czechoslovak census, nearly 17,000 people identified themselves as Ruthenian.

Rusini was actually the name of the inhabitants and territory of a large medieval state centered around Kiev. For centuries their culture was centered on a monastery at Krasny Brod, until the formation of a Greek Catholic bishopric in Presov in 1818.

Traditionally, Ruthenians acted primarily as cattle breeders and farmers, rarely settling in larger towns before the turn of the 20th century. This is still true today, as one can see traveling through the tiny towns with Cyrillic signs that lie in the north-south valleys in eastern Slovakia.

Debated origins

How close to Ukrainian?

There is fierce debate among Ruthenian intellectuals over the ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious origins of the people. Opinions are divided between those who believe Ruthenians to be a distinct group of Ukrainians, and those who campaign for an independent identity with close links to the Russians. In the late 1800’s the two groups were deeply polarized by the emancipation of Ukraine, with one side championing it and the other strongly opposed and hoping to keep friendly ties with mother Russia.

But the one thing both sides had in common was the awful, inescapable poverty of the region and the shortage of land from 1870 until World War I.

Thousands of Ruthenians emigrated to Canada, the United States and Argentina during this time. The most famous Ruthenian of them all, artist Andy Warhol, hailed from near Medzilaborce.

Refused Assimilation

Ukrainian label doesn’t work

Ruthenians were almost assimilated after World War II when Communist Czechoslovakia simply abolished the minority in 1952, recognizing them only as Ukrainians.

Most Ruthenians either balked at the Ukrainian label, choosing Slovak schools over Ukrainian ones, or hardly heeded the ban, living their rural lives, preserving their language, and practicing the Greek-Catholic religion, which was banned in 1950, until better days returned.

After the 1989 revolution, the Ruthenian national movement resurfaced and fought to restore their status, finally codifying their language in 1995. Still, there are so few Ruthenians fighting for recognition that their future as a people is in serious doubt.

End of the millennial struggle

by, Brian J Pozun, 7 May 2001

Vol 3, No 16

Copyright (c) 2001 - Central Europe Review

All Rights Reserved: REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION

Never could it be said that the Rusyns and Hungarians are strangers to one another. From the very beginning of Magyar statehood over one thousand years ago, the two nations have existed side by side. The very fact that the East Slavs, who became the Rusyns, found themselves under Magyar rule for an entire millennium is the crux of the Rusyns' claim to the status of the fourth East Slavic nation; related to, but separate from, the Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians.

While the history of the treatment of Rusyns by the Magyars is not necessarily something that can be held up as a shining example of majority-minority relations, the current policies in force in Hungary certainly can. Now that the Rusyn community in Hungary is counted in the hundreds and not in the hundreds of thousands (as it was before the First World War), Budapest has finally given the Rusyns what they had demanded for a millennium: a degree of autonomy.

Hungary and its minorities

The Rusyns may very well be the oldest minority group in Hungary, but they are by no means the only one or anything close to the largest. The country is currently home to thirteen groups recognized as national minorities. Armenians, Bulgarians, Croats, Germans, Greeks, Gypsies, Poles, Romanians, Serbs, Slovaks, Slovenes and Ukrainians all join the Rusyns in what could be a zoo with most all of the nations of Central Europe—and several more exotic species—on display.

The 1990 census counted Rusyns together with Ukrainians, following standard Eastern-Bloc practice, and found only 674 people speaking either Rusyn or Ukrainian as their mother tongue. Today, Budapest's official estimates say there are 1000 Rusyns in Hungary (separate from Ukrainians), while Rusyn organizations claim the figure is as high as 6000.

Rusyns no longer make much of an impact on Hungarian society. The Rusyn language is used as a significant mode of communication in just two villages, both in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén county in the north-east. One the Rusyns call Mucon (Múcsony) and the other Komloška (Komlóska).

The Rusyn movement in Hungary has made significant progress since taking its first steps in 1991 with the formation of the Organization of Rusyns in Hungary. Several cultural institutions have been created, among them the Andy Warhol Arts Association (1995), the Rusyn Research Institute (1996) and the Rusyn Museum in Múcsony (1998).

Beginning with the 1995/6 school year, eighteen grade schoolers in Múcsony had the opportunity to study in the Rusyn language, and the following year enrollment jumped to 68.

The Rusyn language is also promoted in the media. The community has two primary publications, Ruszinszkij Zsivot/Rusinskyj Život (Rusyn Life), and Országos Ruszin Hírlap/Vsederžavnyj Rusynskyj Visnyk (National Rusyn Newsbulletin). Starting in 1996, channel 1 of Hungarian television began broadcasting a monthly program in Rusyn, and from October of 1997, it has broadcast a weekly Rusyn-language program on channel 2.

Capping off the achievements, Budapest hosted the fourth World Congress of Rusyns in 1997. The Congress, held biennially, is the central event of the international Rusyn community. Representatives of Rusyn organizations from throughout Central Europe and abroad attended the three-day event, and all were impressed with the hospitality showed by the Hungarian capital.

Diversity, real or imagined

Hungary is a highly diverse country, though the sheer number of national groups gives a false impression of this diversity. The thirteen groups that have been granted full national minority protection, however, account for little more than one percent of the total population of Hungary.

Their situation is precarious, given the fact that 40 to 60 percent of adult members of minority groups live in ethnically-mixed marriages, which increases the rate of assimilation into the majority population. International observers believe that minority populations (with the notable exception of the Roma) are fully integrated into Magyar society, a fact which attests to both the reasonable policies of Budapest and to the increasing rates of assimilation.

Out of the goodness of their hearts?

By all accounts, Hungary has instituted what may be the most liberal minority policies in Europe, covering almost all of its non-Magyar residents. The most striking aspect of the policies is the system of minority self-governments throughout the country. International observers has hailed the unique experiment as a significant step forward for minority rights worldwide, even though it is not without its flaws.

The basic document delineating minority rights in Hungary is Article 68 of the Constitution, which grants minorities the rights to collective participation in public life; to use their own languages; to receive schooling in their own languages; and to establish local and national self-governments. A 96-percent majority passed the Act on the Rights of National and Ethnic Minorities in 1993, extending minority rights to have not only a collective but also an individual nature.

In 1996, a Commissioner for the Rights of National and Ethnic Minorities was elected by parliament to act as an ombudsman for minority rights. Also in 1996, legislation was passed which introduced the concept of hate-crimes against national minorities.

All this, however, was not done because Budapest has suddenly taken a liking to its domestic minorities. The overriding motivation was that such large numbers of Magyars live outside the borders of today's Hungary: in Slovakia, Ukraine, Yugoslavia and elsewhere. The general belief is that if Budapest provides its minorities with the highest levels of protection, then it has the right to demand the same levels of protection for Magyar minorities abroad. Even so, the motivation should not belittle the accomplishment.

Self-governance—a bold experiment

The system of self-governance Budapest has established for its minorities is unique in Europe, if not worldwide. In settlements with a significant number of inhabitants belonging to a minority, that minority is permitted by the constitution to establish a local self-government structure with several minority-specific mandates. The members of the self-government are chosen in popular elections.

Additionally, each of the minorities with local self-governments is entitled to form a national self-government in the capital.

The members of the national bodies are elected by the members of the local ones. Though it has not happened as of yet, a group of local self-governments could, theoretically, form a regional tier of minority autonomy.

The basic mandate of a local self-government is to promote the national culture of the minority. It also has the right to consult with local authorities on matters concerning the minority, such as in the fields of public education, culture, media and use of languages.

The national self-governments work in tandem with the national government in the same way. They promote the minority's culture on the national level, and have the right to register content or disapproval with national decisions in similar fields.

Nothing is perfect

Even though the minority self-government system represents one of the highest levels of minority involvement in governance anywhere in Europe, it is faced with several problems that must be resolved quickly in order for the system to function smoothly.

The biggest problem with the system is no surprise: lack of funding. The government must provide each local and national minority self-government with both appropriate facilities to act as a central office and funding according to legislation as well as allocations from the national budget. Unfortunately, the resources made available to the self-governments are, most times, not even close to fulfilling their requirements, and too often programs planned by the self-governments must be scaled back or canceled altogether for lack of funding.

Another concern is the method of electing representatives to the self-governments. As it stands, the elections to self-governments are open to all voters in the country, regardless of whether they actually belong to the minority involved.

Several options have been explored to devise a solution, but none have proved acceptable thus far. The idea of registering members of national minorities was quickly shelved, after it conjured up nightmares of Nazi-era policies. Another suggestion was to have the elections to minority self-governments on a different day from general elections, with the thought that only members of the minority would be inclined to make the effort to vote.

Self-government: the Rusyn experience

The system of minority self-governments came into force when elections to these bodies were held in tandem with the local elections of 1994 throughout Hungary. By the 1998 elections, 1363 local self-government organizations were established, 48 of which actually replaced their municipal administrations and assumed all of their duties. By February 1999, twelve of the thirteen eligible groups had also established a self-government at the national level.

In 1994, the Rusyns founded their first local self-government in Múcsony, and currently there is a total of ten all together. Aside from three in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén county, where the majority of Rusyns live in Hungary, there are also five in various districts of Budapest and another in the municipality of Pest.

The tenth is the national self-government based in Budapest. Rusyns formed the national self-government in October 1998, when local Rusyn self-governments elected the five members of the nation administration. National self-governments are headed jointly by a president and attachés for environmental, media and cultural issues.

After the first elections to national self-governments, the XII district of Budapest was home to just four, serving the German, Croat, Slovene and Armenian communities. With the 1998 elections, four more were created, to serve the Roma, Serb, Greek and Rusyn communities.

While this represented a significant step forward in minority representation in the capital, it came at a price: the district's budget was stretched to the breaking point and it was decided that none of the members of the national self-governments in the XII district would receive the honoraria they had received in the past. For now, this is the only such district in Budapest, but the pattern could easily be repeated elsewhere.

Even though the Rusyns had the bad luck of founding their national self-government in the district with the tightest budget, the self-government has undertaken several important initiatives in the past three years. They have organized dozens of important cultural events and have their own website. They are also working closely with other parts of the Rusyn community.

One of their partners is the Organization of Rusyn Youth, which has set for itself the mission of promoting a Rusyn and European identity among young people, helping them to better themselves; working to help the poor and disadvantaged; preventing drug, alcohol and tobacco use among Rusyn children.

Another major partner is the Rusyn Research Institute in Budapest. With the Institute, the self-government has organized several series of lectures and biannual international conferences of Rusyn studies. Themes from the past two years include "1100 Years of Peaceful Rusyn-Magyar Coexistence: An Example for the Nations of Central Europe" and "The Rusophile Trend in the Rusyn National Renaissance."

The national self-government also promotes the use of the Rusyn language in media. Together with its support and that of the national Foundation for National and Ethnic Minorities, the bilingual black-and-white monthly newsbulletin of the capital was able to introduce a color cover in March 2000, and is now called the Országos Ruszin Hírlap/Vsederžavnyj Rusynskyj Visnyk (National Rusyn Newsbulletin).

In the final analysis...

Since its inception in 1994, Hungary's system of minority self-governments has represented one of the most important steps forward in protection of national minorities to be found anywhere in Europe, if not the world. Given that the thirteen national minorities are an insignificant proportion of the Hungarian population, that it has taken place in Hungary is curious, but also quite important. Due to their small size, the minority populations in Hungary face an even greater threat of assimilation and extinction than more sizable groups elsewhere.

It is impossible to say that the self-governments and Hungarian minority policy have created a utopia for minorities. The self-governments have limited mandates and serve only an advisory role, there is a constant lack of funds for them and their elections are open to all voters. And the government's very motivation for pursuing a liberal minority policy is not necessarily pure of heart. Even still, the self-governments go a long way towards securing the place of minorities in society.

The Rusyns of Hungary are among the luckiest of Rusyn communities elsewhere in Europe. Numerically, they are paltry compared to Rusyn communities in Ukraine or Slovakia, but their situation is significantly better. This fact represents a major historical turnaround. For more than a millennium, the majority of Rusyns in Europe lived in the Kingdom of Hungary, and faced intense official "Magyarization" policies that threatened to destroy the nation.

The Rusyns in the Kingdom of Hungary tried unsuccessfully to gain at least some degree of autonomy beginning in the mid-nineteenth century until the end of the Hapsburg Empire, and again, when Hungary regained control of the then Czechoslovak province of Ruthenia from 1938 to 1945.

The turnaround was so great that Budapest has given the chairman of the Organization of Rusyns a diplomatic passport, making him the only Rusyn "diplomat" in the world. Though it has, unfortunately, come much too late to be of benefit to the majority of Rusyns, it seems that the dream of autonomy has been realized, at least in part, in modern-day Hungary.

by, Brian J Pozun, 7 May 2001

Passaic, New Jersey - 1890 to 1930

by, Joy E. Kovalycsik

In order to compile a detailed family history, the first step (before you view records) is to undertake a comprehensive study of the nature and background histories of individuals who were listed as Ruthenian (also called Carpatho-Rusyns, Rusnaks or just Rusyns.) If you research the social, political, religious structure and attitudes of the past, your entire history, not just a small segment, will be more comprehensible. If this foundation is completed initially research efforts are more rewarding. Also, it will assist your genealogy pursuits by answering many questions beforehand. These questions will no doubt arise during the course of record research.

This essay deals exclusively with Ruthenian immigrants who came to Passaic, New Jersey from the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. Of course, many issues are similar for others who immigrated to other areas of America. You will find differences depending upon areas of research and no one way is absolute. Differences in general (how children were named) to the language (i.e. dialects) will show many disparities due to the area of residence. Those from the areas close to present day Poland may have Polish overtones in their folk tales; whereas, those who came from areas of present-day Ukraine may have a different dialect and pronunciation of words due to interaction with other languages in their regions.

The Ruthenians were a people without a country. The best definition and easiest way to understand this is within the context of the similar category of individuals of Jewish heritage before the birth of the State of Israel. The similarities of the two heritages (minority status, persecution for no good reason, a different language from the majority, different customs, etc.) may speak for how many villages had a respectful interaction with members of the Jewish faith as they were in the same social class. The Ruthenians were a people scattered over a narrow strip of territory that was quite expansive. The Carpathian Mountain regions that were situated within the boundaries of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire encompassed an area of approximately 7,500 square miles. The majority of Ruthenians lived in areas that were not bountiful. These regions followed inefficient agricultural practices, offered poor soil, experienced economic and political oppression and saw a high illiteracy rate (40%), wars and disease. This combination of factors offered substandard existences for many Ruthenians who were generally from what was termed "peasant society" and had few opportunities to improve their station in life. Escaping the various forms of oppression and want was unheard of, outside of death, until the great immigration towards the United States and other countries began in the late nineteenth century.

A good way to understand Ruthenians is to do research from many sources and not just take one researcher’s writings as positive proof evidence. There are many fine reports, books, summaries and information available. The New York Public Library in New York City has a section dedicated to Ruthenians. An excerpt from the book "The Rusyns from Slovakia" by Alexander Bonkalo states "During 700 years of living on the slopes of the Carpathian forest region, the Rusyns participated in Hungarian history by deeds and by suffering." This quote by itself truly does much to identify Ruthenians. As a minority people; and as all minorities were subject to abuse and prejudices; those from the former Austro-Hungarian Empire had limited choices; assimilation to the "party line" of the Empire ensured survival. A review of countless records clearly shows many learned Hungarian and Austrian/German languages; these languages ensured better treatment by authorities and those at higher levels of society. Always keep in mind this was an area ruled by a monarchy and therefore, democracy was not the first order of business. The atmosphere, along with an unfortunate lack of formal education and financial security gave Ruthenians a sense of insecurity and a general attitude of the times to "be quiet and submit." It appears Ruthenians were colonists in what was originally uninhabited territory. Since these areas were rural in nature, it was easier to retain many of their customs and heritage (i.e. language, rituals whether secular or sacred) and this is a potential reason why so many stayed in non-productive areas. The old proverb, well known to the peasant class of Imperial Russia where livestock were treated better than peasant individuals is recalled "The farther you are from the Tsar, the longer you live." This was excellent thinking as the farther (and more remote) you are from centralized government and bureaucratic offices, the better your chances to live in peace.

To give a brief summary of these people and their background prior to the entrance onto American soil, the priest/historian, the Reverend Stephen Gulovich (+1957) described the following: "The Rusins of the nineteenth and early twentieth century’s could really boast of only three classes of people, the clergy, the peasant and the cantor. They had no landed nobility who could champion their case with few exceptions and members of the learned middle class cared very little for their own people and almost imperceptibly became Magyarised (i.e. assimilated into the Hungarian nationality.) The lowly and at times miserable life of the Rusin peasant was shared by the rustic priest who, frequently disliked by his flock, vainly tried to elevate the cultural standard of his people, and by the country man who acted as teacher in the parochial school and cantor in the church. Strangely enough, these three truly typical representatives of the Rusin people could never get together and were constantly at odds." There is also this description which was taken from an official report of the humanitarian bureaucrat Commissioner Edward Egan on the economic conditions of the Ruthenians in Hungary, submitted to the Ministry of Agriculture in 1900: "These people are without land and without cattle, and their destiny lies in the hands of extortioners. They are deliberately induced to drinking and are demoralized to such a degree, that even their own clergy are unable to help them. They are subject to constant harassment and abuse by the administrative powers and no one extends them a helping hand. Morally and economically, these people are swiftly deteriorating and, in the near future, will completely disappear." These statements, which have been written by other authors, were a basic commentary of the Ruthenians at the turn of the century.

The Ruthenians who immigrated to the United States of America were limited initially. The Hungarian records of 1870 reveal only 59 Subcarpathian Ruthenians immigrating, but after 1879 these numbers grew to almost unheard of figures. No doubt the word spread from former immigrants who made the journey back and forth (which was common, especially for males before 1900) and many leaflets were passed out from companies in America looking for inexpensive labor which was required to build American industry. As more and more Ruthenians heard work was available, the stories expanded of wealth and freedom multiplied. This fueled their imaginations to a point where the floodgates opened and great numbers of Ruthenians began the journey to America. Also to be remembered at this time it was not just freedom which forced the immigrants to leave. The European economy at that time was depressed, work was scarce and, in America, they could find more than was available in their areas of residence.

The American Immigration Commission estimates that about 500,000 Ruthenian immigrants had arrived in America by 1897. This figure, although higher than other researchers’ figures, takes into account all those who came from the Ruthenian areas, not just those who stated their national heritage was Ruthenian. A breakdown of numbers for the year 1909 by the American historian Andrew Shipman states figures for areas Ruthenians settled were Pennsylvania 190,000; New York 50,500; New Jersey 40,000; Ohio 35,000; Connecticut 10,000; Massachusetts 7,500; Illinois 8,000; Rhode Island 1,500; Missouri 6,500; Indiana 6,000; Colorado. the Dakotas, Nebraska, and Montana 8,000; West Virginia, Virginia and other southern states 5,000. Of course, this does not take into account those who chose not to identify, for whatever reasons, with their heritage and therefore, figures were probably much higher. It is good to remember in statistic counting, no author who has or will compile figures is totally accurate. There are many census figures and surveys that will not agree with other authors’ research but are given here as a basis to follow. Compiling data in reference to the Ruthenians is difficult at best, since many came here with Hungarian paperwork and were thus classified as Hungarians, Slovaks, or another title. The immigrant, only wishing to gain entrance to America, was not about to dispute a title placed on travel paperwork by government officials as long as they received permission to travel.

According to United States government statistics the greatest number of Ruthenian immigrants arrived here between 1899 and 1914. According to the historian Walter Warzeski's research the peak year being for the Ruthenian immigrant 1914 when the total reached 42,413. The Ruthenians were refugees from poverty and socio-political discrimination which oppressed them in their native lands, but here in America they also experienced some of these same ugly forms of discrimination; sometimes even from the hands of individuals of their own heritage.