Courtesy of George M. Muha

1322 Stephanisau, 1408 Alsoyacabwagasa, Alsowiacobugasa, Felsewiacobugasa, 1497 Jakubiany, 1808 Jakubany; Hungarian: Jakubjan, Syepesjakabfalva; German: Jakobsau; Jakubiansky; Jakubanec.

Szepes County; District Stara Lubovna, Region Presov until 1960; District Presov, Eastern Slovakia Region, Region Presov 1996.

Jankovce, Pod Sipkou, Masa, Zabava.

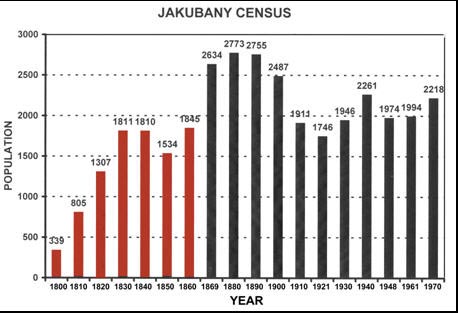

1869-2634, 1880-2773, 1890-2755, 1900-2487, 1910-1911, 1921-1746, 1930-1946, 1940-2261, 1948-1974, 1961-1994, 1970-2218.

1676 HA is the size of the village. HA is short for Hektar. 1 Hektar is 2.471 acres.

The center of the village is 610 meters above the sea level. The surrounding area is between 580-1016 meters above the sea level. Jakubany is situated in the Levocske, in a wide valley formed due to erosion of the Jakubany furrow. There are sulfur springs in the area. There is a river called Jakubianka. Most of the area has been logged a long time ago. The soils are brown. Average temperature is only 4-6 degrees Celsius; July is 14-16 degrees Celsius, January is 5 degrees Celsius. Average yearly rainfall is 700-800 mm and that is almost 3 feet.

The village originated in the 14th century on the property of Lubovnas landlords and it was given by Filip Drugeth in 1322 for inhabitation to Stefan, son of Peter from Lomnicka. He brought in the Slovaks and Germans. The village is mentioned in written records during 1408. During 1412-1772 the village was deposited together with another 12 towns over to polish rule for a loan financing war. In 1497 the hereditary mayor brought in Valachians. In 1760-1870 they had a high burning furnace and were processing iron ore from the surrounding area. The inhabitants were engaged in farming and shepherding. In 1822 serfs revolted against the hard working conditions. During the 19th century many inhabitants emigrated to the USA and Canada. During the present time, people work in industrial factories in larger towns with some still engaged in farming.

There is a curia from the 19th century and the Greek Catholic Church of Sts. Peter & Paul is from 1911, in Seces style, according to design of J. Bobula junior. The village houses are around the main road. There are still some houses standing from the 19th century. There are log houses with stucco outside with courtyards and wood shingle roofs. Log livestock buildings are usually behind the main houses. There are log/hay storage sheds and live stock barns in the meadows. Cattle breeding in the summer months takes place at the meadows and during the summer hay season most of the inhabitants live on the fields which are some distance from the village. The folk costume as in Jakubany was common in several villages of the Poprad and Presov district. They have several of the same elements with different details.

Ron Cieslak aided by Dorothy Kupcho Kosmowski have completed the Herculean task of transcribing over 37,500+ entries in the Parish Registers (Matrika) of the Byzantine (Greek) Catholic Church in Jakubany, Slovakia to computer-searchable databases. Available to all, the databases which covers the period 1772-2004, are currently available online at:

http://www.jakubanyrecords.com

The entries in these Church Registers are ostensibly but a record of births, marriages, and deaths that have occurred in the village. But in fact they are much more in that they also reflect, albeit perhaps obliquely, facts and curiosities about village life.

For example: the entries themselves are for the most part recorded in Latin, the church’s official language – that is except beginning in the 1850’s when the Austrian-Hungarian Empire began an attempt at ethnic cleansing (Magyarization). As a result of an 1851 law, Magyar (ethnic Hungarian) became the official language for all records. Later the entries were made in Russian or Ukrainian script. Clearly ramifications of the changing political alliances within the region are reflected in the church records.

For example: the entries themselves are for the most part recorded in Latin, the church’s official language – that is except beginning in the 1850’s when the Austrian-Hungarian Empire began an attempt at ethnic cleansing (Magyarization). As a result of an 1851 law, Magyar (ethnic Hungarian) became the official language for all records. Later the entries were made in Russian or Ukrainian script. Clearly ramifications of the changing political alliances within the region are reflected in the church records.

Likewise some of the entries in the Observationes column of the Death Registry (which usually record the cause of death) provide a poignant insight. (All given here and below are in translation.) Vanyo Hnasz, age 68, died on 28 Apr 1819 of (cause) “Miserable and desperate”; or the 10 children, the oldest being one year of age, who died in a “whooping cough” epidemic over a two-week period in 1821; or the 106 who died in a calamitous epidemic in 1847/8 of “Hunger/Starvation”; or that of 12 year old Petrus Bjelovoczky who, on 15 July 1903, died while "push(ing) cow across water - fell and drowned”; or the gratuitous remarks about the propensity towards drink included in the entries of those few individuals who "... fell in the well and drowned".

Other entries are revealing: Maria Marchevka-Kopak who at age 37 was “murdered” on 11 Aug 1819; or Stephanus Kundlya, age 10, who was “murdered” on 22 Aug 1852; or 10½ year old Simeonis Marchevka who died on 3 Sep 1856 of “murder”;; or Anna Katrenics, age 35 and a widow who died of cholera on 22 Aug 1873 and “left behind 2 orphan - both parents murdered”. Seemingly human nature is such that violence periodically reached even into a small and, at the time, remote village.

But individual entries aside, the registries can also be view in toto as a collection of numbers – and numbers can be subject to analysis which can lead to other interesting insights into village life. The statistical approach allows many questions to be asked and answered but in the following I develop only three whose answers I found, at least on first viewing, quite startling – those concerning emigration, infant mortality rate, and epidemics.

Village Demographics

To delve into these and related questions will require census data for the village from the 19th through the mid-20th century. Regrettably such collected data prior to 1869 is not available. However this difficulty can be circumvented by calculations using the information contained in the Church's Matrika to estimate the village's population over the period 1800 to 1869.

To delve into these and related questions will require census data for the village from the 19th through the mid-20th century. Regrettably such collected data prior to 1869 is not available. However this difficulty can be circumvented by calculations using the information contained in the Church's Matrika to estimate the village's population over the period 1800 to 1869.

The result is displayed in the bar graph above. The yearly village population obtained from available government records are represented as black bars. Red bars represent the data estimated by analytical techniques (see below) from Matrika data.

On first viewing, the estimates of the population for the interval 1840 - 1860 (red bars) may seem too low for one might expect a roughly linear growth in the village's population linking the years 1830 to 1869. But such is not the case, for during the interval 1838-1850, Jakubany experienced two epidemics during which 36% and then 48% of its population perished – a fact necessarily reflected in the village's population over these years.

Additional demographic information can be coaxed from the marriage and birth/baptism records in the Matrika. Over the interval from 1800-1890 the Jakubany Marriage Register lists 2545 entries and the Birth Registry 12783 entries of whom 2958 died before reaching the age of one. Hence, over this 118 year period, the rough estimate of the number of surviving children per family is four and hence the average family size as six. Since the village population in 1800 is estimated to have been 339, seemingly there were 56 or so families resident in the village at that time. Presumably these 56 arose from the nucleus that raised the first village church (dedicated to SS Kozmos & Damian and built in 1772) and from whose records the earliest data for these calculations is derived.

[Technical note about the calculation – with the government-reported population peak of 2773 in 1880 as a starting point, the algebraic difference between the number of village births and the number of village deaths is subtracted from 2773 to yield the data point for the preceding year, i.e. 1879. The procedure is then repeated with the 1879 data as a starting point and continued back year-by-year to 1800. However before beginning the algebraic manipulations, a "smoothing" of the data is required to correct for the aberrations in the death data due to epidemics. (A six-year moving average was used.) Also note an implicit assumption in this calculation: that it is only by birth and death that individuals enter or leave the village population. Population changes due to emigration or immigration from/to the village are discounted. A survey of sets of family surnames in the Birth/Marriage/Death records indicates population "stability" at least before 1890 when a major emigration began. Hence this assumption is deemed valid.]

EMIGRATION I

Over the period 1869 through 1910, the population of the Greater Hungarian Empire increased from 15.5 million to 20.9 million, a factor of ~33%. The increase would have been much larger – by 2.04 million �� had not this number of individuals emigrated to the United States during the same period. (The emigration statistic was culled from the records of European embarkation ports.)

However this emigration was not uniformly distributed throughout the Empire. Rather five counties – Abaùj-Torna, Szepes, Saros, Ung, and Zemplen – were the principal losers, each with at least 2% of their populations emigrating over the period 1880-1914. At the time, Jakubany was in Szepes County.

Seemingly the loss for Jakubany in particular was much greater for the census bar chart indicates a sharp decline in the village's population over the thirty year interval from 1890 to 1920. At the end of this period there were some 1000 or so fewer people residing in the village - a 37% decrease in its population. The village was not to approach its earlier peak population level for some 50 years (until 1940). Was this decrease primarily due to emigration? Seemingly yes, but then who emigrated and why?

These questions are considered below but first it is necessary to develop information on two other aspects of village life that have enormous bearing on the village's population – the Infant Mortality Rate and Epidemics.

Infant Mortality Rate – Village Health

Infant mortality is formally defined as the number of infant deaths (one year of age or younger) per 1000 live births. However in the present work it is preferable to discuss this rate in terms of a percentage. The conversion is easily made – simply move the decimal point in the formal definition one place to the left to convert to a percentage. For example, a rate quoted as 21.9 deaths per 1000 live births corresponds to a rate of 2.19% when stated as a percentage.

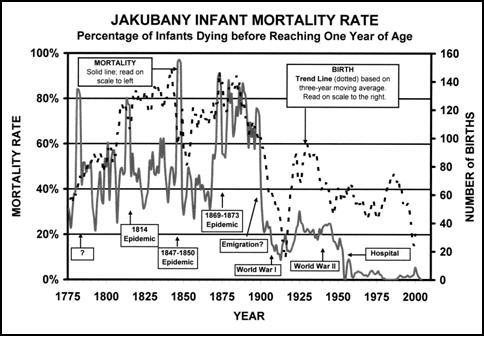

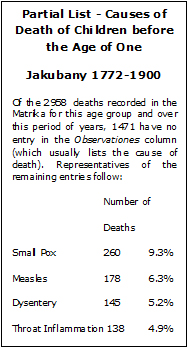

When I first ran a calculation of the infant mortality rate, I could not believe certain of the intermediate results. I recompiled all of the data and recalculated ... with the same astounding result – 50.4% of the children born in Jakubany between the years 1772 and 1890 would die before reaching ten years of age! ... one out of every two! Further, over the same 118 year period, of the 13306 children who were born, 2958 died (~22 %) before reaching the age of one. The results of the complete calculation are shown above as a graph.

When I first ran a calculation of the infant mortality rate, I could not believe certain of the intermediate results. I recompiled all of the data and recalculated ... with the same astounding result – 50.4% of the children born in Jakubany between the years 1772 and 1890 would die before reaching ten years of age! ... one out of every two! Further, over the same 118 year period, of the 13306 children who were born, 2958 died (~22 %) before reaching the age of one. The results of the complete calculation are shown above as a graph.

It is generally held by health organizations that infant mortality rate is a sensitive indicator of a region's health. Studies have shown that in centuries past, the mortality rate in rural areas such as Jakubany fluctuated strongly with climatic conditions, epidemics, and war. The effect of epidemics and war are clearly visible in the plot shown above. The reason usually cited for the correlation with the weather is its effect on the harvest and hence the quality of the population's nutrition.

Note that in the course of a pair of epidemics, in 1847-50 and in 1869-73, fully 90+ percent of the infants did not survive their first year – entire generations were nearly decimated. The sorrow felt in the village must have been wide-ranging and near overwhelming. [The 80% mortality rate in 1790 ( indicated by a "?" on the graph) is discounted as a likely statistical artifact caused by the small number of births/deaths in the sample.]

Another particularly striking feature in the mortality graph above is its precipitous decline beginning ca. 1900. Note that the number of births (dotted trend line on the mortality chart) exhibits a parallel declining behavior. And both the mortality rate and the number of births parallel the 37% decline in the village's population between 1890 and 1920 seen in the census bar graph. If these declines - infant death, infant birth, and village population – were all due to young adults emigrating to the United States before beginning their families, the precipitous decline in the Jakubany mortality rate is readily understood. The entries in the birth/death records in Jakubany would then decrease and those in the United States correspondingly increase.

A second sharp decline in the mortality rate is seen beginning in the 1950's dropping to the 1-2% level where it remains to the present day. Clearly the quality of health care in the village had dramatically improved. It was about this time that the hospital in Stara Lubovna (6 km north of Jakubany) was completed. Rather than at home, birth in a hospital with professional medical personnel in attendance would be expected to greatly lower the infant mortality rate.

A second sharp decline in the mortality rate is seen beginning in the 1950's dropping to the 1-2% level where it remains to the present day. Clearly the quality of health care in the village had dramatically improved. It was about this time that the hospital in Stara Lubovna (6 km north of Jakubany) was completed. Rather than at home, birth in a hospital with professional medical personnel in attendance would be expected to greatly lower the infant mortality rate.

Prior to about 1900 and aside from birth defects, premature birth, and low birth weight, the principal cause of infant mortality worldwide before the age of one, is thought to be due to infections in some general sense. What were some of the common causes of death among the Jakubany children? A partial answer is given in the sidebar at right.

In viewing this 19th century mortality data it is well to recall the state of medical knowledge in that century. For example, although it seems incredulous today, it was not until the mid-1850's that medical science "discovered" that simply washing ones hands before tending to a newborn greatly increased the infant's chance of survival. Further, it was not until the last few decades of the 19th century, that the germ theory of disease had come into general acceptance and the concomitant advances in epidemiology began in earnest.

Given this perspective the 40% range for the Jakubany infant mortality rate from 1810-1875 and less than 2% after 1950 is not grossly unlike the rate world-wide over the same period. For example, in 1900 the US rate was reported to be 16.5% which fell to about 0.7% in 2000. In Slovakia in 2003 the rate was 0.85%.

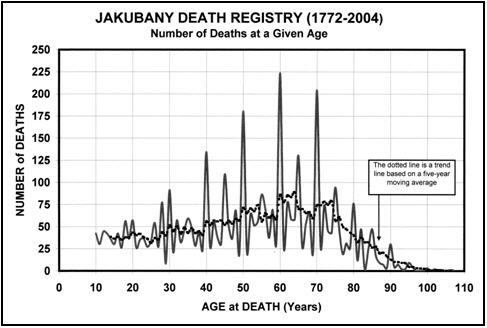

Finally consider those who survived to an age of ten years. How many more years of life could they expect? This is a question of Average Life Expectancy, the rigorous calculation of which is somewhat lengthy. The quality of the Jakubany data does not warrant such an effort for the largest part of the age-at-death data is simply rounded to the nearest multiple of ten. See graph next.

Notice the peaks at each decade marker … 30, 40, 50 … This is certainly an artifact for death does not peak at ages in multiples of 10. Presumably without the deceased available to report their correct age, many of the next of kin simply provided the church scribe with a “rounded” number for entry.

Notice the peaks at each decade marker … 30, 40, 50 … This is certainly an artifact for death does not peak at ages in multiples of 10. Presumably without the deceased available to report their correct age, many of the next of kin simply provided the church scribe with a “rounded” number for entry.

In lieu of the unwarranted rigorous calculation, a weighted-average approximation is provided: those who had survived to the age of ten had an "average life expectancy" of approximately 51 years. For comparison, worldwide the average life expectance in 1900 was 30 years and in 2000 was 63 years of age.

Incidentally through 2004, there were seven people who attained an age greater than 100 years, the oldest surviving for 107 years.

Epidemics - A Fact of Village Life

Over the centuries, epidemics have been a periodic scourge throughout the world. Jakubany was not spared. Indeed, prior to 1890, epidemics were a sad and a major fact of village life. The pre-1900 entries in the Observationes column in the church's Death Registry lists almost every epidemic malady known at the time except malaria.

Over the centuries, epidemics have been a periodic scourge throughout the world. Jakubany was not spared. Indeed, prior to 1890, epidemics were a sad and a major fact of village life. The pre-1900 entries in the Observationes column in the church's Death Registry lists almost every epidemic malady known at the time except malaria.

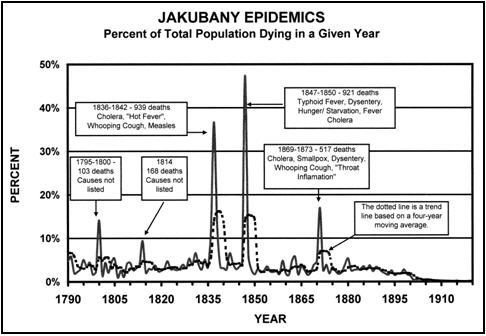

An abbreviated summary of the entries is given in chart form at left. There are five or so major peaks in the plot of the number of deaths versus year, some labeled with the predominant causes of death as listed in the Parish Register for the years.

The most severe affliction to the village occurred in 1847-50 when the second stage of a major cholera pandemic was spreading throughout Europe. The pandemic had begun in India in 1826 and spread in three stages: 1829-1831, 1849-1859, and 1863-1879. It reached Greater Hungary in 1831 and Jakubany five years later. In the first stage and in Austria-Hungary alone, over 100,000 deaths were officially recorded, a number considered a factor of two or three too low by some authorities. Epidemiologists rank this cholera scourge as the worst epidemic/pandemic of the 19th century.

Cholera is listed in the Death Registry as among the major causes of death during Jakubany's first (1827-1842) and third (1869-1873) epidemic outbreaks but surprisingly is listed much less frequently in its second epidemic (1847-50) which was the village’s most severe. It was during these years that the second round of the cholera pandemic was decimating parts of Europe.

Of the 921 deaths in Jakubany during its 1847-1849 epidemic, typhoid fever or simply "fever" are listed as the cause of death for 278 individuals (30%) with cholera listed for 132 (13%). The 921 deaths constitute about 47% of the village's population at that time. With the village almost half decimated one can speculate that perhaps the crops in the field were not planted or harvested, the live stock not tended, etc., thereby accounting for the 106 deaths (12%) recorded as due to "Hunger/Starvation" during that period.

As concerns the two remaining peaks in the epidemic graph, 1795-1800 and 1814, the Observationes column in the Registry list no cause of death for any entry during these periods. Localized epidemics of smallpox and cholera were prevalent throughout Europe during these years with a major typhus outbreak in nearby Russia in 1814.

In the post-1890 era in Jakubany, major epidemics seemingly were a thing of the past as evidenced by the absence of any major peaks in the post-1890 years on the chart above. Curiously, the next major world-wide scourge, during the years 1917-1920, seemingly bypassed Jakubany. This was the "Spanish Flu" pandemic which is held to be the worst epidemic of the 20th century just past.

EMIGRATION II – OVERPOPULATION

A 1946 study conducted by Geographical Institute, Faculty of Natural Sciences of Bratislava University in Slovakia cites Jakubany’s land area as 16,300 acres with agriculture "… of a low standard … (due to) … bad soil and rough climate …" (but also chiefly due to ) "… bad farming of the fields." This study also notes that only 24.4% of the land area was suitable for agriculture.

In 1800 the ca. 4100 tillable acres available, if apportioned among an estimated population at the time of 339 people, corresponds to an allotment of about 12 acres per person. In 1890, because of the village’s eight-fold population increase, the equivalent allotment was about 1.5 acres per person.

Would the 12 acres/person, presumably adequate to support a Jakubany resident in 1800, be sufficient when reduced by a factor of eight in 1890? It seem unlikely, for in 1946, with a population of only 80% that of 1890, the Bratislava University study also notes that the village's harvest was only 2/3's sufficient in meeting the cereal food requirements of the village.

If not in 1890, then certainly within a decade or so, an overpopulation problem would have arisen. If population growth was not checked, a village dependent solely on subsistence agriculture and livestock care and breeding could not sustain itself. The effect of the pair of major epidemics in the village from 1835 through 1850 seemingly only delayed for a time any reckoning with the problem.

Certainly the evidence suggests that by 1890 something "had to give" ... and seemingly it did. Over the next three decades the village's population decreased by 1000 (37%) for in 1890 the emigration from the village began en mass. It continued for the next twenty-five years, to be brought to a halt by the outbreak of World War I in 1914 complemented by the restrictive US immigration laws enacted in the early 1920’s.

Did those who emigrated intend to remain away permanently? Seemingly not all, for several years ago the Port of Hamburg (Germany) reviewed their departure and arrival records for the years 1850-1934 and concluded that one third of all immigrants to the US eventually returned to their homeland, never to return again to the US. The US Immigration Service, using a different scheme of calculation, arrived at a slightly higher estimate (35%).

It is thought that these returnees, after accumulating some savings while working in the US, returned to their motherland, perhaps intending to purchase land, but certainly intending to remain henceforth in the comfortable surroundings of family and friends with familiar language and customs. [My maternal grandparents chose this course ... but then quickly reversed direction and returned to the US ... see below.]

A problem of overpopulation such as this might have been resolved by expanding the agricultural base to include manufacturing-exporting thereby providing additional employment opportunities. Indeed, from the mid-1850's on, such was the underlying trend throughout northwestern Europe as the Industrial Revolution began its general transformation of society. But in Jakubany at that time, the required capital, technical expertise, and infrastructure to permit such an expansion was undoubtedly lacking.

Emigration III - Who Emigrated?

There can be little doubt that it was predominately the young people that were emigrating. Septuagenarians were not likely to undertake the ardors of an ocean-crossing on a cramped passenger liner. By 1890 if not earlier, the future as viewed particularly by the young likely appeared bleak and circumscribed. And as a group the young took to emigration in earnest. The move was primarily to the United States but other northern European countries were also chosen destinations.

With the ready availability of the online Ellis Island Arrival Records (for 1892-1924), it is a straight-forward, albeit lengthy, exercise to accumulate from these records a sufficiently large sample to document this conclusion for any given family.

In the instance of my direct-line ancestors (Rusinak/Kupcha), the results of such a compilation follows: by the early 1900's, of the 29 individuals of the 15 fourth-generation Jakubany families that had immigrated to the US, 26 of the 29 (90%) were under the age of 22 and 20 (70%) were teenagers or younger. The oldest (and earliest arrival) was 39 when he arrived in the US in 1894.

The last departure of my direct-line family from the village was in 1921. With the passing of all in the earlier generations in the village coupled with the emigration of the entire fourth generation, the year 1921 also marks the end of my family line in Jakubany. (The line traces back to three brothers constituting the first generation and whose records are listed in the 1790's in the Jakubany Matrika.)

The Ellis Island Records often also include an entry listing the final US destination of the immigrant. Reviewing these entries provided yet another observation concerning my family's social diaspora: at least initially, members of the three family branches (i.e. of the three brothers) understandably chose to settle close to others of their branch in areas where employment was readily available – in the coal-mining regions of either northeastern or western Pennsylvania or the steel-fabricating centers of Indiana. However over the four decades after arrival in the US, most moved on to other employment and to other states. The final resting places of the fourth generation are now marked by headstones in cemeteries in Indiana, Ohio, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania.

It is likely that Jakubany, along with many other cities, towns, and villages in the Austria-Hungary of the past, suffered long-term consequences from the massive 1870-1920 Hungarian emigration of their young. For it is the young who provide the entrepreneurial spirit, resourcefulness, vitality, and diligence necessary to continually improve and enrich the quality of life for all of the population.

Emigration IV – War & Military Service

Without question the matter of survival coupled with a prospect of a bleak future was the predominant cause for emigration. Yet I suspect that another reason, not commonly discussed, was at least an auxiliary consideration – dread of war and, for males, the concomitant required military service. For females, conscription of their husband for military service meant disruption in family support and family life.

Documentary evidence of my suspicion is meager. I present only anecdotal evidence collected during conversations with relatives while compiling my family's history. But, after conversation with other doing genealogical research on their own families, my suspicion has only been strengthened.

Consider that in the late 19th century all physically-fit males in the Austro-Hungarian Empire were subject to military conscription – usually two years of active service in the Landswehr (Hungarian conscripted militia) followed by 10 years in the reserves. Conditions in the Landswehr in the 19th century were reportedly so harsh that service therein was described by one author as “… a sentence of death … wives simply gave up hope of ever seeing their drafted husbands again.”

My maternal grandfather was one of the drafted husbands. In 1903, after six years of his working in the coal mines of Western Pennsylvania during which my grandmother carefully saved a part of his earnings, my grandparents (Rusinak/Kupcha) and their first child returned to Jakubany, bought some land, and settled down to raise a family.

But within fifteen months after their return to Jakubany, my grandfather was struck by misfortune – he was conscripted in the village's military lottery for service in the Landswehr. Entered on his service record (of which I have a complete copy) is a 1906 notation that he had served his required time on active duty and was transferred to the reserves for ten years of additional standby service.

Would he "standby" in Jakubany? Not a chance. For within three months (!) of his discharge, my grandfather had returned to the US – never to return to Jakubany. In his haste to leave he had left his wife and two children in Jakubany. An 1906 Ellis Island Arrival Record documents his abruptly arranged travel. He was headed to a western Pennsylvania coal mine near Baggaley, PA. My grandmother remained in Jakubany to dispose of their newly acquired land. The family reunited in Pennsylvania two years later.

[Sidelight: My grandfather became a naturalized citizen of the US in 1921, curiously the same year that the efficient Czech military bureaucracy formally discharged him from the Landswehr as being "overage". In contrast, Slovakia's bureaucratic procedures were seemingly slow – legal transfer of my grandparent's land in Jakubany was not completed until 1976 – 30 years or so after my grandparent's passing. (I also have complete records of the land transaction and its intermediate steps.)]

Another anecdote also on my maternal side: the wife of one of my relatives related that her father-in-law’s disdain of military service was so intense that he abruptly cancelled his imminent marriage and left Jakubany in 1897 for the USA “… via the rear door while the recruiters were coming in the front door.” (His betrothed later joined him and they were married in Indiana.)

Family members of the three other of my maternal-side relatives relate similar tales concerning military service.

On the paternal side of my family (Muha/Mulesza) I personally recall occasions on which my grandfather recited details of his service in the Hussars (Hungarian Light Cavalry). His comment that “… they treated the horses better than the men … (and that it was) ... no good over there, always fighting" made a lasting impression on me ... I was a young boy at the time. My grandfather recalled that border clashes were a common event making activation of the reserves a frequent occurrence and thereby disrupting village and family life. He and his wife (with child – my father) arrived in the US in 1903 and 1905 respectively. They never returned to Hungary, not even for a short visit.

Finally it is well documented that in the late 1890's evasion of military service by emigration was considered to be a growing problem. Indeed, by 1903 the military manpower situation in Hungary had become acute and Hungary added a requirement that any male seeking to leave the country had to produce a copy of his Landswehr discharge papers for inspection. At Hungary's insistence, the German Federal State cooperated by requiring this same proof to be presented at the German Ports of Embarkations prior to boarding any of their ships.

In retrospect, although it seems clear as concerns my ancestors, I am left to wonder to what extent military service was a determinant in the decision of others to emigrate.

References

Military Requirements Within The Austro-Hungarian Empire by Joe Strana

www.tccweb.org/odds&ends.htm [Downloaded: 24 Aug 01]

Medical Knowledge – 19th Century

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germ_theory_of_disease

www.timelinescience.org/resource/students/pencilin/germ_th.htm]

Bratislava University Study – Jakubany

www.jakubanyrecords.com/JakubianyHistorySummary1946.doc

Climate and Georesources – Jakubany

http://geotur.tuke.sk/pdf/2010/n01/05_Complova_v1_n1.pdf

Hamburg (Germany) Port of Embarkation:

http://www.emecklenburg.de/Mecklenburg/en/hambrg.htm

By John Mitchell, jmitchell@insidevc.com

Re-produced here with permission of the author.

This article originally appeared in the Ventura County Star

Passport Photo via CIA.gov

Dec. 2 - I will not forget that day for the rest of my life. The wind was blowing so hard that it turned people over. Our eyebrows and hair changed into bunches of icicles. Our clothes and shoes were frozen, hard as a stone."

Dec. 2 - I will not forget that day for the rest of my life. The wind was blowing so hard that it turned people over. Our eyebrows and hair changed into bunches of icicles. Our clothes and shoes were frozen, hard as a stone."

"I didn't have any gloves and could feel my hands freezing stiff. I couldn't do anything about it. In the afternoon, we were all dead tired, but we didn't dare sit down even for a moment. We later saw those partisans who tried it -- and froze stiff. We later counted 83 of them."

It is November 1944. A blizzard is raging on the freezing slopes of Mount Dumbier in Slovakia. The speaker is Maria Gulovich Liu, of Oxnard, who is recalling an unforgettable World War II experience. She was running for her life with American and British intelligence agents, Allied airmen, Czech soldiers, French and Slovak partisans and others. Chasing them were German soldiers led by a determined SS commander. Many dangerous miles to the east were the advancing Russians and safety.

The scene is described in a new book, "World War II: OSS Tragedy in Slovakia," by Jim Downs, a former U.S. Army counterintelligence agent. The book, which Downs put together from the remembrances of survivors and from the files of the U.S. Office of Strategic Services and the Slovak and Czech governments, vividly chronicles a desperate journey in which the then-23-year-old Maria Gulovich played a life-saving role.

War Mission

The backdrop for this extraordinary adventure is an OSS attempt in the fall of 1944 to drop agents into Slovakia to assist a Slovak uprising against the Germans and to rescue downed U.S. airmen. But once the agents were in Slovakia, German SS divisions crushed the uprising and sent the agents -- called the DAWES team -- fleeing into the mountains. When it was all over, 12 American and three British agents, an Associated Press correspondent and an American woman were dead.

Of events on Nov. 12, Downs writes: "Just before midnight they reached a point on the west slope of Mt. Skalka. Chilled to the bone, they built a fire by a stream. Maria took off her boots only to discover one of her feet was frozen black.

"A Jewish doctor with the Czech brigade told her to rub snow on the foot. Several men had frozen big toes. Later, Maria couldn't get her boots back on. Associated Press reporter Joe Morton had the same problem. They wrapped their feet in rags. Some put on wooden sabots (shoes)."

Morton, who later would be captured and executed by the Germans, shared his supply of sulphur with her.

"That was what probably saved my foot," Liu said Friday, showing her scarred foot. "Even today, when it gets cold, I feel the pain in it," she said.

First Mission

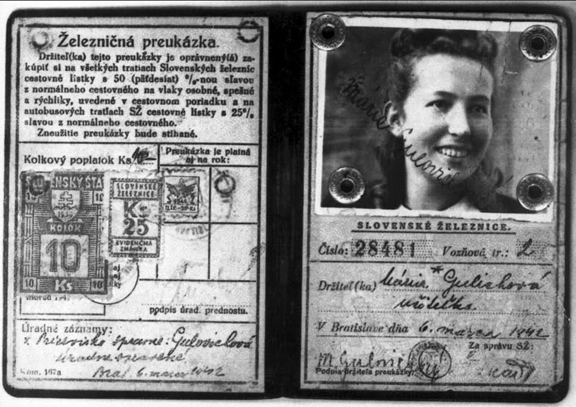

Prior to her involvement with the OSS, the young, innocent-looking Maria Gulovich, a school teacher, had been coerced into doing spy work for the Slovak underground and, later, for a Russian liaison officer to the Czechs.

On her first mission she was sent 65 miles to pick up a suitcase, not knowing what was in it. On her return train trip, she "smiled coquettishly" at a German SS officer, and twice the gentleman officer carried her suitcase, avoiding inspections. It wasn't until 1989 that she learned there was a radio in the suitcase. She probably would have been shot if she had been caught.

Eventually, she was assigned by a leader of the Czechoslovakian Forces of the Interior to act as an interpreter for the American OSS officers.

For more than four hard months, Gulovich and her Allied comrades fought terrain and weather while fleeing the Germans, then had to put up with interrogations by Russian NKVD (secret police) members, who locked them up in displaced person camps. Prior to reaching the "safety" of the Russian front line, members of the group were captured by the Germans or split off in other directions. Those who stayed with Gulovich eventually made it to freedom.

Years later, U.S. Army Lt. Bill McGregor, who survived capture, SS interrogation and imprisonment, said in the book that "everybody was in love with Maria. She was really a brave young woman, making all those food runs" -- many of them under the noses of the Germans.

U.S. Army Sgt. Ken Dunlevy, who escaped with Gulovich, called her "our little sweetheart ... for whom I am and will be grateful forever. To her, it is no doubt that I owe my safety and perhaps my life."

Gulovich and the three agents with her -- Dunlevy, U.S. Army Sgt. Steve Catlos and British Sgt. Bill Davies -- did not get a true taste of freedom until April 1945 in Bucharest, Romania.

The Russians were taking them to Odessa, Ukraine. At a train stop, American and British authorities swooped in and whisked the four away, infuriating the Russians. Gulovich was taken to the British Mission in Bucharest, where she remained until the war ended on May 8. Even then, because exit visas from Romania had to be approved by the Russians, she feared arrest by the NKVD. In wasn't until July that she was able to board an American C-47 and fly to freedom in Italy.

Quiet Life

Today, the 81-year-old Maria Gulovich Liu lives a quiet and peaceful life with her husband, Hans, and an amenable house cat, Beranie, in Oxnard's Rio Lindo neighborhood.

She's been a resident of the city for 39 years, has worked as a real estate agent for Century 21 and Cosby-Tipton and served on the Rio Lindo Neighborhood Council.

She talks with pride about her two children from a previous marriage, Eugene, an environmental scientist, and Lynn, a veterinarian, both living on the East Coast. She disappears for a moment, then returns with a framed photograph of a pretty girl she introduces as Lisa, her grandchild.

In many ways, the war is not a distant memory for her.

"For a long time I didn't think about it because I was busy," she said. "Now, with more time to reflect and working with Jim Downs, I think it was a miracle that I and the rest of them survived.

"By all the rules, we shouldn't have, but somebody upstairs helped us. That's the only way I can explain it."

She still harbors anger at the Germans and the German-controlled Slovak government during the war.

Vivid in her mind are the events of March 19, 1939, almost six months before Adolph Hitler attacked Poland.

As usual, she reported to school to teach her second-grade class.

"We were told we were having an assembly, and when we got there I saw that the pictures of the Slovak officials had been removed and in their place was a picture of Josef Tiso," she said. "I started crying. I knew we had lost our independence."

A pro-German and former Catholic monsignor, Tiso established a police state that included allowing German textbooks in Slovak schools.

"I recall September 1939," Liu said. "My family lived only about 20 miles or so from the Polish border. Nearby was the main road to Poland.

"For days and nights you saw German soldiers, their weapons, their horses with new leather reins -- I can still smell that leather. For two weeks, they never stopped going by."

Liu said it gave her great pleasure in 1944 to see the Germans retreating from the Russian front.

"It was so different from before," she said. "It was a ragtag army in beat-up trucks. I am a sympathetic person, but it did my heart good to see them struggling in."

Post war years

After the war, Liu met Allen Dulles, later the director of the CIA, and through his help, and the help of OSS head Gen. "Wild Bill" Donovan, she was allowed to immigrate to the United States with a scholarship to Vassar College, then a renowned women's school, in Poughkeepsie, N.Y.

On May 25, 1946, at the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, Donovan presented Liu and several others medals for their service during World War II.

At first, Liu was going to receive a Distinguished Service Cross, but because she wasn't a citizen that was deemed inappropriate, Downs wrote in his book. Then a Silver Star was considered, but that, too, was rejected because she was a woman. In the end, she received a Bronze Star for her heroic and meritorious actions. She was also the first woman to be decorated on the Plain of West Point in front of the Corps of Cadets.

That night, Liu was escorted to a dance called The Hop at West Point by an upper classman hailed as "Buster."

"He liked to talk about Glenn Davis, Doc Blanchard and Elizabeth Taylor," Liu remembers. "When I came here I didn't have a notion of how America came to be or anything else about it. I had no idea what he was talking about."

As a guest of the government, she was given a room at the hotel on campus. She smiles now as she says about a week after she got back to Vassar she received the hotel bill, which she had to pay.

In 1994, she was invited to the Slovak Republic for the 50th anniversary celebration of the uprising against the Germans. A photo of the event shows her chatting with U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.

During a phone conversation last week, Downs said that while he was researching his book he learned that Liu "was still kind of a legendary person among Slovaks. I've been to the Slovak Embassy in Washington, and they all know about her.

"When I talked to Bill McGregor, he was in a rest home dying of Alzheimer's. He couldn't remember what he had for breakfast, but he remembered the war.

"He said everyone was astonished at how Maria was able to fade into the landscape. But she was loyal and stuck with the Americans, who were also astonished at her bravery."

Note: Maria Gulovich lived in Jakubany before becoming a teacher. Her father Edmund Gulovich was Jakubany's resident Greek Catholic priest from 1925-50.

A Slovak village embraces its Greek Catholic heritage

by Jacqueline Ruyak

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

A boy readies the saddle for the family’s new pony. (photo: Andrej Bán)

A boy readies the saddle for the family’s new pony. (photo: Andrej Bán)

Last December, on the feast of St. Nicholas, a group of excited preschool children gathered around a priest in a classroom in the remote village of Jakubany in eastern Slovakia. Father Damian Saraka was there to usher in an annual custom; to greet the beloved St. Nicholas and his scary sidekick, the devil. This year, the young Greek Catholic priest had another reason for attending the event. Dorothy, his daughter, sat among the giddy children.

Every feast of St. Nicholas, the bishop and his less than saintly companion visit Jakubany, checking whether or not children know their prayers. St. Nicholas rewards those who do with candy and other goodies. The devil threatens to punish those who do not.

Under communism, authorities discouraged the custom in favor of the more secular Santa Claus. But in this Rusyn Greek Catholic village, residents flouted the restriction and continued to host the saint and the imp, impressing upon their children the necessity of prayer.

Before his current assignment in Jakubany, Father Saraka lived and worked for five years in a hamlet of 80 people near Slovakias border with Ukraine — his first parish after his ordination to the priesthood in Prešov. Alcoholism was rife in the tiny community and only four men had jobs.

“When people came to the house to do some work,” the priest remembered, “they would first ask for alcohol. To them, it was like putting gas in a car.”

In Jakubany, things are different, he said. Villagers want to work.

As elsewhere in eastern Slovakia, the country’s least developed region, unemployment in Jakubany runs high. The few jobs available — almost exclusively in the construction, service and teaching sectors pay poorly. This dearth of opportunity compels young villagers to look for work in Slovakia’s larger urban centers or in the neighboring Czech Republic. Young, unmarried men often share information about available jobs even further afield, such as Britain, Ireland or the United States.

“Younger people move to the nearby town of Stará L’ubovňa for work and get flats or houses there,” said Mária Pol’anská, the school’s director. “Open borders [within the European Union] allow a lot of people to go abroad to look for work. Some come back, some don’t.”

Mrs. Pol’anská has four children and six grandchildren, but none live in Jakubany. “My children married and went off to Stará L’ubovňa, to Holland and elsewhere. They talked about who would stay and take over the family home, but in the end they all left.”

While Mrs. Pol’anská has considered leaving Jakubany and joining members of her family, she has decided against it for now. “My home is here, my old mother is here.”

Recent migration has not yet depopulated the village of its 2,500 residents. The municipality has invested considerable sums to improve infrastructure. A new road was built and an updated sewage system is being installed. There are also plans to construct new apartment buildings.

“The population has now stabilized,” said Michal Kundl’a, village historian and a retired teacher. To lure back those who left, the village has made land available at low rates. “We hope those who went abroad will return and build their own homes.”

But Jakubany may not be able to hold back migration’s sting much longer. More than a third of its population is over the age of 60 and, with few job opportunities, many young families struggle to stay afloat. According to Mrs. Pol’anská, the number of children in preschool has also dropped from 73 to 56 in recent years.

About 300 students, including a growing number of Roma, attend the village’s only public school, which includes classes from first through ninth grades. For high school, students from Jakubany travel to nearby Stará L’ubovňa or Prešov.

Until recently, village youth rarely went to university. For many years, careers in the skilled trades —carpentry, masonry and plastering — promised a comfortable living, particularly in Britain or North America. These days, a growing number of Jakubany’s young people, lured by the prospect of lucrative professional careers abroad, are now setting their sights on a college education.

At the village school all students must take a course in religion or ethics. Most choose religion class, which Father Saraka and a colleague teach. The priest also teaches a section specially designed for Roma students.

Unlike the Rusyn majority, the number of Roma children in Jakubany has increased in recent years. None are enrolled in the preschool. For the most part, if a Roma child attends preschool, he or she does so intermittently and is considered by the school as a “visitor.”

According to the school’s director, not sending children to preschool is a relatively recent trend. Under communism, she explained, all children enrolled in the program, mainly because the government closely monitored attendance.

“Maternity leave and benefits were tied to attendance,” said Mrs. Pol’anská. But under democracy, people are free to do as they want: they must take the initiative to do it.

“Roma usually choose not to send their children to preschool.’

Over the past five years, Jakubany’s Roma community has grown from about 600 to 800 people, now making up about a third of the village’s total population. To assist the increasing number of Roma students, the school employs a first–grade teacher, who is Roma and speaks the Romany dialect used in the village. Most Roma children speak Romany as their first language and many need individual help with Slovak.

In addition to teaching religion to Roma students, Father Saraka celebrates the Divine Liturgy at the Roma chapel each week and visits Roma parishioners in their homes. Father Saraka laments the widespread anti–Roma stereotypes, particularly among older villagers. But he remains optimistic that attitudes toward Roma are changing for the better, at least among the younger generation.

“A priest’s role is to evangelize and to lead people to a spiritual life. My work is to say that through Jesus comes truth and light. My work is to show the way,” he said.

The earliest historical record of Jakubany dates from 1322, when the governing nobleman of Stará L’ubovňa ordered the construction of a new village. Initially called Stefanoce, the village’s name changed to Jakubany about 1348.

Poor Rusyn shepherds and farmers first settled there, clearing the surrounding forests for pastures and fields. For centuries, this distinct ethnic Slavic group has lived in scattered communities throughout the mountainous Carpathian region.

While Jakubany remains overwhelmingly Rusyn, historical circumstances have often blurred the villagers’ ethnic identity. “In the First Republic [1918-39], people were Rusyn, then Slovak, then Ukrainian. Then they got scared and chose to be Slovak, but spoke Rusyn,” explained Mr. Kundl’a.

Most of Jakubany’s residents speak Rusyn, even if they have a mixed ethnic heritage. Though his father was Slovak, Mr. Kundl’a speaks Rusyn. The son of a priest, Father Saraka is also ethnic Slovak, but he grew up in a Rusyn village. As do most Greek Catholic priests in Slovakia, he celebrates the Divine Liturgy in Church Slavonic and Slovak. He hears confessions, however, in Rusyn.

When iron was discovered in the nearby mountains in the early 19th century, Jakubany experienced a population boom, peaking at 2,800 villagers in 1825. But when the iron ran out, the village gradually declined. Most of those who remained worked in the forests. Economic depression in the first half of the 20th century — particularly during the World War II era — hit Jakubany hard, driving many villagers to emigrate to the United States or Ukraine.

In the 1950’s, Communist authorities imposed collective farming and seized nearby forests, restricting access only to the military. Dramatically, these measures changed Jakubany’s way of life. By the 1970’s, large contemporary residential buildings designed for multigenerational use replaced many of the village’s traditional small log houses. Most of the remaining relics now lie uninhabited. Ironically, during much of this period, Jakubany enjoyed its highest level of prosperity and stability.

“Jakubany is a very Greek Catholic village,” said Father Saraka. “And traditions are very strong here. Their faith and traditions help the villagers keep their Rusyn identity.”

A parishioner raises a candlestick as a symbol of light during the Greek Catholic Divine Liturgy. (photo: Andrej Bán)

While Jakubany had always been Greek Catholic, Czechoslovakia’s post–World War II Communist government suppressed the church and forced its members to enter the Orthodox Church, whose Byzantine rites and traditions they shared. When Jakubany’s Greek Catholic pastor refused to comply, he was imprisoned and replaced by an Orthodox priest, who was largely ignored by the villagers. Many clung to their Greek Catholic faith at home, only attending church services during special occasions, such as weddings.

In 1968, amid a period of liberalization known as the Prague Spring, a Greek Catholic priest returned to Jakubany. When he tried to reclaim the parish, his Orthodox counterpart refused to leave. For four weeks, the Greek Catholic cleric celebrated liturgies outside the parish church. Taking matters into their own hands, villagers eventually removed the Orthodox priest from the church. The police arrested 10 people, sentencing each of them to two years in prison. For a time, authorities again banned the celebration of the Greek Catholic liturgy.

At the center of the storm was a striking stone structure, Italianate in style, dedicated to Sts. Peter and Paul. Villagers built the church about a century ago after the original wooden one, then dedicated to Sts. Cosmas and Damian, burnt. The present church dominates the village, serving as its focal point and principal tourist attraction.

“The church is very much the center of the community here,” said Father Saraka. “It helps older people keep their traditions and younger people to understand them better.

“But we have a problem with people observing religion as they would a tradition. Traditions are not the purpose of faith: they should help people with their faith.

“When young people leave,” the priest said, “they often lose their faith as they lose their traditions. I want to help them realize the beauty of life lived in accord with Jesus.”

Girls wearing traditional dress participate in Jakubany's Easter celebration. (photo: Father Damian Saraka)

Jakubany has a rich cultural heritage, including distinctive folklore, music, dance and dress. Villagers developed traditions in relation to their deep, historical relationship with the forests, pastures and mountains that surround the community.

“People here were woodlanders, living in forest chalets and gathering mushrooms,” said Michal Kundl’a, the village historian. Mr. Kundl’a has studied Jakubany’s history since his college years. He also established a folklore society, which he ran for 27 years.

When Father Saraka first came to the village, however, the folklore society no longer held meetings. Sensing something was missing, Father Saraka encouraged Mr. Kundl’a and others to revive the group.

“Everyone still knew the songs, but they weren’t doing anything with them. I asked about the folklore group and lit a small fire, but it was the people here who took it and made something big of it,” recalled the priest.

Active again, the folklore society now organizes seasonal events and takes part in regional festivals and competitions. For religious celebrations, many villagers wear hand–stitched costumes and perform time-honored dances. But these traditions are not limited to special occasions. Most older women still wear traditional dress to church.

Father Saraka also encouraged Mr. Kundl’a to write a book on the village’s history and its traditions. Taking the priest’s advice, Mr. Kundl’a wrote the book, which was published in 2004. An instant sensation locally, it sold out in two weeks. Currently in its second printing, it is now being translated into English.

In 2005, a group of Americans whose parents or grandparents emigrated from Jakubany visited the village. Everyone in the village got caught up in the excitement.

“They prepared some special presentations for the visitors,” said Father Saraka. “When they saw how well that went, people really got involved.” The priest himself exhibited some of the 9,000 photographs he has taken documenting village life.

“My business is your business,” said Father Saraka with a smile when describing relations among the village’s residents. In Jakubany, neighbors rank second only to family. For generations, extended family lived and worked close to one another, often sharing households. Even today, most of the village’s elderly live with their families. But, Father Saraka worries that the village’s traditional family is disappearing.

“Contemporary children probably won’t grow up to take care of their parents because their parents are away at work all day. That changes family relations. Fewer families live and work together as in the past. More men with families are leaving to work abroad, which also changes family dynamics.”

Yet despite changing economic and social pressures, residents keep positive. Helena Knazovická and Magda Dzedzinová, preschool teachers, tell a joke about the people who live in Jakubany. Once long ago, a plane flying over the village crashed nearby. The passengers who landed on their feet ran away, while those who landed on their heads stayed in Jakubany. The women laughed, but then quickly listed reasons never to leave. They boasted that Jakubany had the best air in central Europe, the cleanest water, the most beautiful nature – no matter what season – perfect for swimming, hiking, mushrooming, skiing and skating, and of course the best goulash parties around.

“People here are openhearted mountain folks. They are used to speaking their minds and moving on. They’re ordinary people, helpful and willing,” said Mr. Kundla.

“They love their priests, especially this priest and the last one. Neither has held himself above the people. Both have taught that love is the best thing we have, that rich or poor we can help, give to and love one another. They have strengthened the faith of people who remain here.”

Those Who Served in Religious Orders

Father Stephen V. Gulyassy

Stephen V. Gulyassy was born in Jakubany, present day Slovakia, on *February 11, 1891 the son of Stephen Gulyassy a Greek Catholic farmer and Anna Hrebik also a Greek Catholic. He was baptized on Febrary 14, 1891 by Fr. Stephen Zubriczky at the Greek Catholic Church of Sts. Peter & Paul in Jakubany. His godparents were John Macsuga a Greek Catholic farmer and Anna Loboda a Greek Catholic unmarried woman.

After immigration to the United States, he received his elementary education within the Homestead and Pittsburg, Pennsylvania school system. Upon graduation from Saint Vincent’s College Preparatory School (1908 to 1914) he undertook his seminary training at Saint Mary’s Roman Catholic Seminary, Baltimore, Maryland and Saint Vincent’s Roman Catholic Seminary. He married Gabriella Dzurma in 1919 in Braddock, Pennsylvania and was then ordained to the Greek Catholic priesthood on September 7, 1919 by the Most Reverend Nicetas Budka, D.D., at the Ukrainian Catholic Redemptorist Monastery in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

Father Stephen served in various Greek Catholic parishes. Some of his assignments included Saints Peter and Paul, Braddock, Pennsylvania, Saint Michael’s Greek Catholic Church, Allentown, Pennsylvania, Saints Peter and Paul Church, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, Saints Peter and Paul Greek Catholic Church, Phillipsburg, New Jersey, Saint Michael’s Greek Catholic Church, Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, Saint John’s Greek Catholic Church, Cleveland, Ohio and Saint Nicholas Croatian Greek Catholic Church, Cleveland, Ohio. Father Stephen was also instrumental in founding Saint Stephen’s Greek Catholic Church, Euclid, Ohio in 1955.

Father Stephen Gulyassy died on Tuesday, January 11, 1966 in Parma, Ohio. At the time of his death, he was survived by his wife Gabriella (Dzmura) Gulyassy, his son Victor who was legal counsel for the Byzantine Catholic Churches of the Cleveland area and his daughter Gabrielle Kinkela. Another son, Dr. Nicholas S. Gulyassy, M.D. pre-deceased Father Stephen in 1951. Funeral Mass was held on January 14, 1966 at Saint John’s Byzantine Catholic Church, Parma, Ohio. The Most Rev. Nicholas T. Elko, D.D., Bishop of the Pittsburgh Byzantine Catholic Diocese officiated. He was interred at Holy Ghost Greek Catholic Cemetery, Cleveland, Ohio.

Photo Credit - Jeffrey Shorf, Sr. (Findagrave.com)

*U.S. Records Indicate October 13, 1890