Background

What is the Byzantine (Greek) Catholic Church?

Saints Cyril & Methodius

The Byzantine Rite Catholic Church is one among many rites within the church. The history is traced in unbroken continuity back to Jesus Christ and the Twelve Apostles. The primacy of the Catholic Church was begun with the martyrdom of Peter and Paul; the succession of bishops continues unbroken to our present day.

The Pope, as head of the Catholic Church, has many titles. He is Bishop of Rome, and Vicar of the Universal Church among them. The most familiar rite of the church is the Latin or Roman rite. However, there are over 20 rites within the Catholic Church. All are connected by their allegiance with the Holy See which started with the primacy of Saint Peter. The largest of the eastern rites is the Byzantine Rite. The Byzantine liturgy is based on the service developed by Saint James for the Antiochian church. Later, this liturgy was modified by Saint Basil the Great (329-379) and Saint John Chrysostom (344-407). Some of the churches who utilize the Byzantine rite while incorporating their own traditions and expression are Albanian, Belarussian, Bulgarian, Croatian, Greek, Hungarian, Italo-Albanian, Melkite, Romanian, Ruthenian, Russian, Slovak and Ukrainian. In 862 Saints Cyril & Methodius brought the gospel to the area of Great Moravia. From here the faith spread as far as western Ukraine. In the regions further east the faith was received in the year 988. The Byzantine Rite Catholic Church began during the missionary years of Saints Cyril & Methodius.

The Byzantine Catholic Churches reflect customs of Greek, Byzantine and Semitic cultures. The name has its origins in the ancient title of the city of Istanbul (Constantinople) or “Byzantium.” The people who resided within the Carpathian Mountain areas of Eastern Europe expressed their universal Catholic faith in conjunction with practices of the Christian East. Their never ending ties to the See of Peter were formalized in 1595 at the Union of Brest in Lithuania and reaffirmed in 1646 at the Union of Uzhorod. These were embraced and respected by the Austro-Hungarian Empress Maria Theresa. They were given the name “Greek Catholics” in deference to the origin of their liturgy. The church has her own hierarchy (i.e. bishops, priests, religious) who are subject to the leadership of the Holy Father in Rome. The head of the Byzantine Catholic Church in America is called a metropolitan.

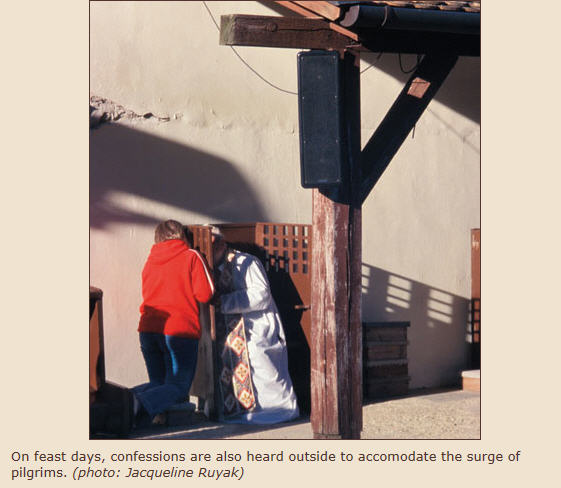

In the United States, during the 1950’s the term “Byzantine Rite Catholic” was implemented. This change sought to identify the rite with its liturgical origins from Byzantium. The Byzantine Catholic Church is steeped in a rich tradition and retains her distinctive features. Baptism and Chrismation (i.e. Confirmation) are performed at the same time, Holy Communion is received under both forms given by the priest from the chalice on a spoon. Confession can be face to face or within a confessional. The Sacrament of Holy Unction (called the Last Rites at times by both Latin and Eastern Rites) is not only for those who are dying, but, for those who are experiencing illness. Marriage and Holy Orders complete the seven sacraments of the Byzantine Catholic Church. Some differences from the Roman rite and the Byzantine rite are the Byzantine Catholic Church operates under a different code of canon law. The church also has a different liturgical year with distinctive feasts and saints.

There are additional Lenten fasting periods such as the Nativity (i.e. Christmas) fast, the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul and the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. While the Roman Rite liturgical year begins on the first Sunday of Advent, the Byzantine Catholic liturgical year begins on September 1st. Also, while a celibate clergy is standard for the Roman Rite, in the Byzantine Catholic Church married clergy were the tradition. In the United States this practice was discontinued but in Eastern Europe it remained. In 2014, the Holy Father reintroduced the married priesthood for America. Some similarities to the Roman Catholic Church are First Holy Communion observances, praying the Holy Rosary, Statues of the Virgin Mary and various saints, devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus and kneeling out of respect during consecration. While these practices are identified with the Latin Rite, they were gladly incorporated and are endearing to the faithful of the Byzantine Rite. It is interesting to note in many Roman Catholic churches the beauty of icons have become popular and are displayed for veneration. This is one such example of adapting worship practices within the universal church. Many in the Roman Catholic Church are not aware they can fulfil their Sunday obligation in a Byzantine Catholic Church and vice versa.

On each feast day the practice of Mirovanije or anointing with Holy Oil, is given. The priest places a cross of blessed oil on the forehead of each parishioner at the end of the service. During particular periods of the year, there are various greetings among the faithful. Some are Glory to Jesus Christ! Glory Forever! Christ is Born! Glorify Him! Christ is Risen! Indeed He is Risen!, Christ is Among Us!, He is and Always Will Be!, Christ is Baptized!, In the Jordan!. As to liturgical music, only singing (Prostopenie or Chant) is performed by the human voice. In a Byzantine Catholic Church, no musical instruments are permitted and the congregation is led by a cantor to sign responses and hymns. There are also specific services, some being Vespers (a night service), Presanctified Liturgy (held during lent), Moleben (a prayer service of intercession which can be offered in honor of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary or a particular saint or topic as in the case of war, famine, etc.,) and Panikhida (a specific service for the soul or souls of the deceased.) Bells play an important part in Byzantine Catholic worship. They are rung to call the faithful to prayer prior to services and remind the congregation of the solemnity of the words of consecration for Holy Communion. Lastly, at the beginning and the end of a funeral they are rung, per tradition, to denote the trumpets which will sound at the last judgement when the dead shall rise. Bells also adorn chains of the censer when the priest swings it. There are twelve bells which represent the twelve apostles. Again, these bells draw attention to the service at the altar. The only day that bells are never rung is Good Friday.

The interior of a Byzantine Catholic Church is different from a Roman Catholic Church. The altar is separated from the pew area by a screen (iconostasis) with two middle doors (i.e. Royal Doors). To the far left and right are smaller doors which are named “Deacon’s Doors.” This screen that contains various icons can be very large (i.e. tier upon tier) or very basic. The first row of the screen however must contain the icon of Christ (on the right side of the royal doors), the Virgin Mary on the left, then the saint or feast the church is dedicated to is at the far right. At the far left is an icon of Saint Nicholas, who was named as the patron of the Greek Catholic (Byzantine Catholic) church. Unlike the Roman Rite, in the Byzantine Rite the priest faces the altar when saying Liturgy (Mass).

There are some Byzantine Catholic Churches who do not utilize an iconostasis. This was done as it was a preference of the parishioners but makes the church no less Byzantine Rite. When entering a church the faithful bow to the altar rather than genuflect. They bless themselves from right to left rather than left to right as is the practice in the Latin Rite. There are various special blessings during the liturgical year such as the blessing of fruit, flowers & herbs, candles and decorating of the church with green branches and leaves for the Feast of Pentecost. Another unique feature of the church is on Palm Sunday. On this day, pussy willows are blessed and issued along with palms. This tradition goes back to areas in Eastern Europe where no palms were available. In January of each year the blessing of water takes place. This tradition symbolizes Christ’s baptism in the river Jordan. After the blessing, the worshipers take blessed water home for use during the year.

St. Michael's Cathedral in Passaic, New Jersey did not have an Iconostasis until the 1980's

Candles and incense play a very important part of the service. The priest incenses the gifts, the altar and the people. Candles on the altar remind the faithful Christ is the light of the world. They are also lit in designated areas of the church for the faithful to say prayers for the living and the dead. Also, in honor of the true presence, each church has an “Eternal Light.” This candle, which burns continuously, is generally hung from the ceiling in front of the altar. The soft glow of the candle reminds all worshipers Christ truly dwells on the altar.

The church is the recipient of a continuous chain from the first Apostles down to our present time. The Byzantine Catholic church while steeped in tradition is alive and serves all. While a repository of many traditions and customs, these are adapted to modern times. The church is an invaluable treasure of rich liturgical tradition. This experience of the sacred, beauty and grandeur of services give worshipers a presence of heaven on earth. Everyone is invited to visit the Byzantine Catholic Church and experience this ancient rite which for centuries has been as is mentioned in The Creed, the One, Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church!

The Carpatho-Rusyn Greek Catholic Churches

by Michael J.L. La Civita

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

Morning sunshine fills St. Basil the Great Church in Krajné Cierno, Slovakia. (photo: Andrej Ban)

For more than a millennium, Central Europe’s Carpatho-Rusyns have been engulfed in a violent whirl of Magyar, Germanic and Slavic antagonism. Always subjugated, Rusyn peasants toiled the soil, kept the livestock or cut the timber of their Hungarian, Austrian or Polish masters. Such conditions, coupled with centuries of serfdom and forced assimilation, hardly favored the development of a distinct Rusyn identity. Nevertheless, among the Rusyns such an identity did develop, sowed by their distinct Slavic language, nurtured by their Byzantine Christianity — which they received from Sts. Cyril and Methodius in the late ninth century — and reinforced by their full communion, or unia, with the church of Rome.

Today, fewer than 900,000 Rusyn Greek Catholics are scattered throughout Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, North America, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Ukraine. A unified church, gathering them all under one mantle, does not exist. Rusyn Greek Catholics — also called Ruthenians — make up three distinct churches that, while sharing the same origins, traditions and culture, remain independent of each other.

• In the United States, the Metropolitan Byzantine Archeparchy of Pittsburgh, with its three dependent eparchies of Parma, Passaic and Phoenix, is a particular or sui iuris church. It includes about 93,000 members.

• The Eparchy of Mukacevo in Subcarpathian Ukraine, which numbers about 375,000 people, is dependent directly on the Holy See.

• The Apostolic Exarchate for Byzantine Catholics in the Czech Republic is also dependent on the Holy See and counts 178,000 members.

Rusyn Greek Catholics also belong to various jurisdictions of the Greek Catholic churches of Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, Ukraine and the former Yugoslavia. Complicating matters further, substantial numbers of Rusyns, all formerly Greek Catholic, have created communities within various Orthodox churches in North America, Poland and the Czech and Slovak republics. However, with the exception of the American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church — an eparchy formed in Pittsburgh in 1939 under the jurisdiction of the ecumenical patriarchate in Constantinople — their Rusyn identity has largely eroded.

Origins. As the churches of the East and the church of Rome parted company — particularly after the Great Schism in 1054 — Rusyn peasants scattered throughout the Carpathian Mountains of Central Europe remained attached to their Orthodox Byzantine Christian faith.

Though they shared the same customs and rites as their northeastern neighbors (modern Ukrainians), Rusyns adapted these rites, making them their own. Fortified by the monks of St. Nicholas Monastery, an ancient foundation located near Mukacevo (a town in modern Ukraine), Rusyns built their unique wooden churches, wrote their icons and sang their plainchant, or prostopinije, all contributing to the creation of a distinctive Subcarpathian Rusyn Orthodox church.

Though held in contempt by the Hungarian ruling class, Rusyn bishops served as both secular and spiritual shepherds. Bishops came from the local community and were elected by a council of monks from St. Nicholas Monastery.

Cataclysmic events in the 16th and early 17th centuries — the Protestant Reformation, the Ottoman Turkish invasion of Central Europe, the decline of the Hungarian kingdom and the rise of the Austrian Hapsburg dynasty — altered the fortunes of the Rusyns and the confessional dynamics of the region.

In April 1646, in the chapel of the castle in the city of Užhorod, 63 Rusyn Orthodox priests entered into full communion with Rome. Supported by his priests’ profession in Užhorod and fueled by the zeal of the monks of St. Nicholas Monastery, Parfenii Petrovych, Orthodox bishop of Mukacevo, led his entire church into full communion with Rome less than 20 years later.

Until Pope Clement XIV erected the Greek Catholic Eparchy of Mukacevo in 1771, however, Rusyn Greek Catholic bishops functioned as vicars of the Hungarian Roman Catholic bishops of Eger. And Rusyn priests — most of whom were married — were subordinate to Hungarian Roman Catholic pastors. In 1780, the seat of the Rusyn Greek Catholic bishop, while retaining its ancient name, moved from Mukacevo to nearby Užhorod, where a seminary had been established a few years earlier.

Rusyn awakening. The 19th century, particularly after the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, ushered in an intellectual movement that sparked the rise of national movements throughout Europe, including one among the Rusyns.

Led largely by Rusyn Greek Catholic priests from the eparchies of Mukacevo and Prešov (erected in 1818), this stirring of Rusyn consciousness inspired the publication of the first Rusyn-language primer, the documentation of ancient folk songs and hymns and the creation of lyric poems and stories. Works such as “The Song of the Evil Landlord” and “Life of a Rusyn” give some understanding of the lives of the Rusyns under their Hungarian rulers. With the creation of the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy in 1867, a rejuvenated Hungarian government unleashed an aggressive campaign to wipe out a national movement among its Rusyn citizens — ironically, the same sort of movement that had inspired a Hungarian uprising against Austrian Hapsburg rule less than 20 years earlier.

Though most Rusyn Greek Catholic leaders opposed this campaign of assimilation, several bishops (particularly those in Prešov) went along with it, suppressing the use of Rusyn in schools and asserting a Hungarian identity.

Distressed by this assimilation policy, the self-appointed “Godfather of all Slavs,” Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, encouraged Greek Catholic Rusyns to return to Orthodoxy, which he claimed would uphold Rusyn traditions. The move also destabilized the multinational Austro-Hungarian Empire, Russia’s rival.

This “back to the old faith” movement outlived the Dual Monarchy, Hungarian sovereignty of the Rusyn Subcarpathian homeland and the tsar. It reached a climax in the 1920’s, when tens of thousands of Greek Catholic Rusyns — citizens of the newly created Czechoslovakia — embraced Orthodoxy.

Emigration. Beginning in the late 19th century, an estimated 200,000 Rusyns immigrated to the United States, settling in the industrialized areas of Connecticut, Indiana, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia. Lured by employment agents of the mines and mills, they quarried coal and forged steel, enriching their employers and building a nation. And though working conditions were wretched, many Rusyn immigrants believed they lacked nothing except a church in which they could worship God in keeping with the traditions of their ancestors.

Fueled by faith and freed from the oppression choking the old country, Rusyn immigrants banded together. They formed associations and, from the collected dues, donations and interest-free personal loans, they built their churches, modest reminders of home.

The Greek Catholic Union, a fraternal organization founded in 1892 in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, provided economic, legal and moral support to many emerging Rusyn Greek Catholic parishes. Contrary to the usual Roman Catholic practice in the United States, however, the Rusyn laity, with the backing of the Greek Catholic Union, not only built but owned their churches. And the priests who celebrated the sacred mysteries, while sent by their bishops, were solicited, retained and supported by the trustees of the parish. Also contrary to usual U.S. Roman Catholic practice, most of these priests were, in keeping with the norms of the Greek Catholic tradition, married.

Crisis and schism. Wounded by cries of “Americanism” and “Modernism” hurled by critics in Europe — and unfamiliar with Greek Catholic traditions — some U.S. Roman Catholic bishops (who had oversight of Greek Catholic parishes) denied married or widowed priests the faculties necessary to carry out their ministries.

Father Alexis Toth (1853-1909), the son of a Greek Catholic priest, a former seminary professor and a widower from the Rusyn Greek Catholic Eparchy of Prešov, sought the jurisdiction of a Russian Orthodox bishop in San Francisco. He did so after Roman Catholic Archbishop John Ireland of St. Paul denied him the faculties to guide a Rusyn Greek Catholic parish in Minneapolis.

In 1891, the parish embraced Orthodoxy, launching a pro-Orthodox movement among American Rusyn Greek Catholics. By the time of Father Toth’s death, more than 25,000 Rusyn Greek Catholics in the United States entered the Russian Orthodox Church. Ironically, their acceptance of Russian Orthodoxy subsequently contributed to the loss of their Rusyn traditions and the acceptance of a more dominant Russian identity.

This movement prompted the U.S. Greek Catholic community (which in addition to Rusyns included Croats, Hungarians, Slovaks and Ukrainians) to petition the Holy See for a Greek Catholic bishop, which, they hoped, would be able to represent their church with equanimity and defend their rights and prerogatives.

Bishop Soter Ortynsky’s arrival in the United States in August 1907 coincided with the publication of “Ea Semper.” This apostolic letter delineated the new bishop’s duties (an auxiliary to Roman Catholic bishops) and modified several Greek Catholic customs and practices, calling for withholding confirmation from infants at baptism (the sacrament was to be conferred on persons of suitable age by bishops, not priests, as in the Roman Catholic tradition) and stipulating that married priests were not to be ordained in the United States or sent from abroad.

Sensing the erosion of their Greek Catholic identity, Rusyn-Americans protested the appointment. Bolstered by their fraternal societies, Rusyn-Americans also identified the bishop as an advocate of the apostolic letter, a friend of the Ukrainian nationalist movement and, therefore, their foe.

Following the bishop’s death in 1916, the Holy See established two separate Greek Catholic administrations (in 1924 these were elevated to apostolic exarchates). One was erected in Philadelphia for Ukrainians and a second in Pittsburgh for Greek Catholic Rusyns, Croatians, Hungarians and Slovaks. By 1929, there were some 150 Rusyn Greek Catholic parishes throughout the United States, embracing almost 300,000 members.

The calm that followed the erection of the exarchates, however, did not last. In 1929, a new decree from the Holy See, “Cum Data Fuerit,” enforced not only clerical celibacy, but called for the legal transfer of all church properties to the respective Greek Catholic bishops. The decree shook the entire Greek Catholic community, regardless of ethnic background.

The desire of Rusyn-Americans to maintain their Eastern Christian faith, or stara vira (old faith), and the privileges and rites associated with it, would eventually split the community. Though the Rusyn Greek Catholic Exarch of Pittsburgh, Bishop Basil Takach, requested that Rome reconsider its stand on the ordination of married clergy in the United States, some 37 Rusyn Greek Catholic parishes rebelled and eventually sought union with the Orthodox ecumenical patriarchate of Constantinople. Today, 75 parishes and missions, numbering more than 50,000 people, make up the American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church.

New World stability. Despite these bewildering conflicts, the Rusyn Greek Catholic Church in the United States flourished. Perhaps in response to its earlier ethnic trials, its bishops encouraged an “American” character after World War II.

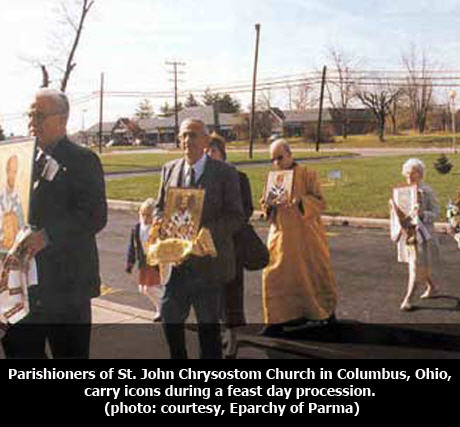

This Americanization of the Rusyn Greek Catholic Church, however, tended toward Latinization. An abbreviated Divine Liturgy was now recited in English; use of the church’s lovely plainchant in Church Slavonic all but disappeared. And in many churches, the iconostasis, or wall of icons separating sanctuary and nave, was reduced, simplified or removed; side altars with Byzantine-style images, resembling the ordering of Roman Catholic sanctuaries, were erected in their place. Nevertheless, participation in church activities was highly enthusiastic and vocations to the priesthood and religious life increased.

In 1963, Pope Paul VI divided the Apostolic Exarchate of Pittsburgh into two eparchial sees. One eparchy was established in Pittsburgh and a second in Passaic, New Jersey. A third was created in 1969 in Parma, Ohio. That same year, Paul VI established the Eparchy of Pittsburgh as a metropolitan see, with Passaic and Parma as suffragan sees. In 1981, Pope John Paul II created a third eparchy in Van Nuys, California, which has since moved to Phoenix.

European revival. After World War I, communities that made up the Rusyn Greek Catholic eparchies of Mukacevo and Prešov were incorporated into the newly created republic of Czechoslovakia. But trouble surfaced in 1939 when Hitler dismembered the republic, absorbed Czech lands and created a fascist Slovak puppet state that ruthlessly suppressed ethnic minorities, including the Rusyn Greek Catholics of Mukacevo and Prešov.

At the conclusion of World War II, the Soviets annexed parts of the Subcarpathian basin — including Mukacevo and neighboring Užhorod — and incorporated these Rusyn areas into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Prešov remained in Soviet-controlled Czechoslovakia.

The Soviets ruthlessly persecuted the Rusyn Greek Catholic Church. They shut the doors of the seminary in Užhorod in 1946, murdered Bishop Theodore Romža of Mukacevo a year later and forced Rusyn Greek Catholics into the Orthodox Church in 1949.

The Soviets and their allies squashed any lingering remains of a Rusyn Greek Catholic identity, driving such sentiments underground. The church, nevertheless, survived. The Greek Catholic Eparchy of Prešov in Czechoslovakia was restored after the liberal government reforms of 1968; however, the Rusyn Greek Catholic eparchy assumed a Slovak identity, which it retains to this day.

In Soviet Ukraine, the Eparchy of Mukacevo resurfaced in 1989, but its Rusyn identity was questioned and tried. In 1993, the Holy See reaffirmed the eparchy’s unique relationship to the Holy See, declining to incorporate it into the much larger Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.

In 1996, Pope John Paul II erected an exarchate for Greek Catholics in the Czech Republic, officially classifying it as a “Ruthenian” jurisdiction. The exarchate was created, not only to care for the pastoral needs of Greek Catholic Rusyns and Slovaks living in the Czech Republic, but to regularize the orders of married Latin priests ordained secretly during the Communist era.

While a unified church may not yet exist, European and North American Rusyn Greek Catholics work together, assisting one another with financial and personnel support. This support is not limited to Greek Catholics alone. Guided by the ecumenical movement and encouraged by the foundation of nonpartisan societies dedicated to the study of Carpatho-Rusyn genealogy, history, literature and religion, relations among Rusyns of all faiths press forward. On the occasion of the centennial anniversary of the printing of the first official compilation and manual of the prostopinije (late June 2006), the then apostolic administrator of the Greek Catholic Eparchy of Mukacevo, Bishop Milan Sasik, C.M., invited all eparchies rooted in the church of Mukacevo, Greek Catholic and Orthodox, to a conference in Užhorod.

“Our liturgical plainchant tradition identifies us, unites us and distinguishes us as one church in the Byzantine tradition,” he said. “The testimony of this common usage is an important reason to celebrate together.”

Michael La Civita is CNEWA’s Assistant Secretary for Communications.

Hungary

The Hungarian Greek Catholic Church

by Michael J.L. La Civita

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

For centuries, Hungary dominated the culture, geography and socioeconomic life of Central Europe. Its defeat in World War I, however, cost the nation three- quarters of its territory, all of its coastline, a third of its population and much of its diverse demography. Today, Hungary is a landlocked and largely homogeneous country — a shadow of its former self.

In Hungary’s rural northeast — near its borders with Slovakia, Ukraine and Romania — one small community of faith offers a glimpse of Hungary’s multiethnic past. Sheltered by the Carpathian Mountains, some 290,000 people — ethnic Hungarians (Magyars), Gypsies (Roma), Romanians, Rusyns and Slovaks — make up the Hungarian Greek Catholic Church, Byzantine in tradition and in full communion with the church of Rome. While each ethnic group maintains its own proud history and traditions, they together have forged a dynamic church authentically Hungarian, Byzantine and Catholic.

Origins. According to early medieval chroniclers, Byzantine missionaries working among the Slavs in the ninth century first encountered nomadic Magyar tribes as they began to settle in the Carpathian Basin. A number of Magyar chiefs, to secure their hold on the land, traveled to the then center of power, Constantinople. There, they established an alliance with the Byzantine emperor and were baptized and received into the Byzantine church.

Sarolt, the daughter of one such clan leader, married the heir of the Árpáds, the chief Magyar family. Their son would later embrace Latin Christianity, take the name Stephen and, after receiving his crown from the pope in the year 1000, forge a united Magyar realm closely allied with the Latin West.

Stephen did not favor the Byzantine church of his mother, but it nevertheless flourished. Several important medieval relics, including the Holy Crown of Hungary, the coronation robe and a renowned reliquary of the true cross, demonstrate the influence of Byzantium. While the crown is largely a Byzantine work, the robe and reliquary are attributed to Magyar artisans living in Hungary’s Byzantine monasteries.

Though the churches of the Byzantine East and the Latin West parted company after the Great Schism in 1054, Hungary’s Byzantine Orthodox Christians, Magyars and Slavs, remained attached to their form of the faith.

The realm’s Orthodox, however, were later decimated by the Mongols, an Asiatic nomadic tribe who invaded Hungary in the middle 13th century and destroyed the kingdom’s towns, villages and monasteries. Historians believe half of Hungary’s people were killed in the onslaught; the Mongols carried off many of the survivors.

Turks and Flux. Eventually, Hungary recovered from the Mongol invasions. Its kings gathered up the survivors, consolidated their power and established a sprawling Central European nation anchored firmly in the traditions of the Latin West.

Even as Hungary expanded, it confronted a new enemy. The Ottomans, a Turkish Muslim tribe originally from Central Asia, conquered Byzantine territory in Asia and Europe as they migrated west. In 1453, they took Constantinople; from there the Ottoman sultans subdued the Balkans with its Albanian, Bulgar, Greek, Jewish and Slavic peoples. As they pushed deeper into Central Europe, they repeatedly clashed with the forces of the Hungarian king.

Orthodox Christian Serbs, fleeing the Turks, found refuge in the Hungarian province of Vajdaság, now the autonomous Serbian province of Vojvodina. In exchange for cultural and religious freedom, the Serbs formed a guard to defend Hungary’s borders. Nevertheless, the Turks advanced deeper into Hungary. Thousands of Serbs fled north of the capital of Buda, establishing Szentendre, a Serbian community that remains rooted in its Slavic heritage and Orthodox faith.

The decline of royal authority, due to the rise of the landed gentry who had embraced the Reformation, crippled Hungary. In 1541, Ottoman forces crushed the Hungarians in battle and captured Buda. In the confusion that followed, Hungary was divided into three parts, Royal Hungary — seized by the Austrian Hapsburgs Ottoman Hungary and Transylvania, which became an autonomous principality under the suzerainty of the Ottomans.

The Orthodox faith of Transylvania’s Romanian serfs, who made up the majority of the population, was held in contempt by the Hungarian nobility, most of whom had become Lutherans or Calvinists. Denied financial support and legal personality, the Orthodox Church in Transylvania declined. As the Ottomans retreated from Central Europe, the Catholic Hapsburgs rushed into the vacuum, absorbing Hungarian lands. Tightening their grip, the Hapsburgs introduced the Jesuits in the late 17th century to re-Catholicize the Hungarian realm.

Hungarian Greek Catholics. Following the Ottomans’ loss of Buda and central Hungary in 1686, Greek Catholic Slavs — Rusyns and Slovaks — emerged from the protection of the dense forests of the Carpathians and settled in Hungary’s plains. These Greek Catholics, under the protection of the bishop of Mukacevo, had entered into full communion with the Roman church only a generation earlier.

As with their coreligionists in Transylvania, Hungary’s Orthodox hierarchy (most of whom were Rusyns) had received assurances from the Jesuits that, in exchange for their loyalty to the papacy, the Orthodox would retain their liturgical rites, customs and privileges, including a married clergy and the method of electing bishops. In addition, their clergy would be granted the same civil rights and privileges extended to Roman Catholic clergy — important considerations in the Catholic Hapsburg realm.

Until Pope Clement XIV erected the Greek Catholic Eparchy of Mukacevo in 1771, these Rusyn Greek Catholic bishops functioned as vicars of the Hungarian Roman Catholic bishops of Eger. And Rusyn Greek Catholic priests, often married, were subordinated to Hungarian Roman Catholic pastors.

The Jesuits reached out to the Hungarian Protestant community as well. In the 18th century, a significant number entered the Catholic Church, choosing not the Roman but the Greek Catholic Church. These new Hungarian Greek Catholics were placed under the pastoral care of the Rusyn Greek Catholic hierarchy, who employed Church Slavonic in the celebration of the sacraments. This prompted many of these former Protestants to lobby for the use of Hungarian in the Divine Liturgy, which was met with resistance among church authorities.

Nevertheless, the first Hungarian translation of the liturgy of St. John Chrysostom was published, privately, in 1795.

The 19th century, particularly after the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, ushered in the Romantic Era. This cultural and intellectual movement sparked a rise of nationalism throughout Asia and Europe, impacting Hungarians, Romanians and Rusyns.

This stirring of ethnic consciousness prompted the publication of language primers, the documentation of ancient folk songs and hymns, the creation of lyric poems and stories and the rise of competing national aspirations. In this era — which also inspired the Hungarian revolt against Hapsburg rule and the subsequent creation of the Duel Monarchy of Austro-Hungary — scholars published Greek Catholic liturgical books in Hungarian. Church authorities did not approve their use.

Perhaps to placate Hungarian nationalists, the Austro-Hungarian emperor founded a Hungarian Greek Catholic vicariate in Hajdúdorog in 1873.

To celebrate the 900th anniversary of St. Stephen’s coronation as king, thousands of Hungarian pilgrims, Greek and Roman Catholic, visited Rome. Greek Catholics petitioned Pope Leo XIII to sanction the liturgical use of Hungarian and to raise the vicariate to an eparchy.

In June 1912, Pope Pius X elevated the vicariate to an eparchy and assigned to it 162 Hungarian-speaking parishes. But, he decided that Greek should be the liturgical language of the church. He instructed the clergy to learn it within three years. World War I intervened, however, and the papal directive was not enforced. After the war’s conclusion and the dismemberment of both the Dual Monarchy and the Hungarian realm, the remaining liturgical books were published in Hungarian and met no opposition.

Today. Originally, the Greek Catholic Eparchy of Hajdúdorog embraced only Hungarian-speaking parishes in eastern Hungary and the capital of Budapest.

In 1924, the Holy See established an exarchate in Miskolc for the Hungarian Rusyn-speaking Greek Catholic parishes that once formed a part of the Eparchy of Presov. (After World War I, Presov had become a part of the newly formed Czechoslovakia.) The distinct Rusyn identity of these parishes, however, faded. They increasingly became integrated into Hungarian culture and replaced Church Slavonic with Hungarian. Interestingly, Presov had been the center of a Hungarian assimilation movement within the Greek Catholic Rusyn community from the 19th century.

Since World War II, the Apostolic Exarchate of Miskolc has been administered by the bishop of Hajdúdorog, whose authority now extends to all Greek Catholics living in Hungary.

Under communism, Hungary’s Greek Catholics were spared the persecutions suffered by Greek Catholics in Romania and Ukraine. Though religious communities were closed, priests and religious dispersed, 134 schools shuttered, catechesis limited and nonliturgical activities monitored, the church survived. In 1950, Bishop Miklós Dudás, O.S.B.M., established a seminary within the walls of his residence in the town of Nyíregyháza. While youth programs and sodalities were prohibited, parish pilgrimages to Máriapócs, a little Greek Catholic village famous for its miraculous icon of the Virgin Mary, continued with great enthusiasm.

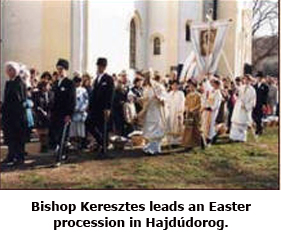

With the collapse of the Iron Curtain, Hungary’s Greek Catholic Church surged to fill the void left after a half-century of despotic rule in Central and Eastern Europe. Led by Bishop Szilárd Keresztes, the Eparchy of Hajdúdorog collected icons, liturgical books, vestments and other sacramentals, which he immediately offered to the once banned Greek Catholic churches in Romania and Ukraine.

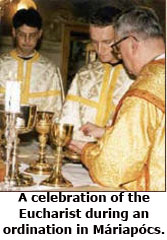

Because of its central location, Bishop Keresztes suggested the eparchial seminary — which is dedicated to St. Athanasius — should play a key role in the revival of Europe’s Greek Catholic churches. In 1990, he opened it to Romanians, Rusyns, Slovaks and Ukrainians interested in the priesthood. To improve the quality of the education offered there, the bishop invited an impressive number of foreign educated professors. As a result, the theological faculty became an affiliate of the Pontifical Oriental Institute in Rome in 1995.

Formation of lay catechists also figured prominently in the life of the church soon after the collapse of communism. In 1992, the bishop signed an agreement with the Teachers Training College in Nyíregyháza and set up a corresponding department at the seminary for the formation of teachers.

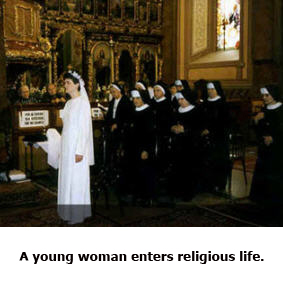

The Hungarian Greek Catholic Church shares in the socioeconomic challenges affecting the country. Even as birthrates continue to fall, driving down the number of men and women entering priesthood and religious, the demands placed upon the church grow.

Increasingly, Greek Catholic priests are working to diffuse tensions between Hungary’s growing Roma minority and ethnic Magyars. And the depopulation of Hungary’s eastern rural villages, the traditional center of the Greek Catholic Church, is affecting family and parish life. Yet, Bishop Keresztes, now retired, remains optimistic.

“Young people will be the future church. They are looking for religious life, even if they are doubters or critics and do not accept everything about that life,” he said in these pages in 2007.

“Today,” he said, “we have to accept that the church is criticized, sometimes with reason, but despite this we have to show people the beauty of our Christian values.”

Hungary’s Greek Catholics

A brief profile of the Hungarian Greek Catholic Church.

text by Dr. Janka György

photographs by Miklós Erdös

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

According to Byzantine chronicles, missionaries met Hungarian tribes in the course of their wanderings throughout Central Europe and, in the middle of the 10th century, baptized a number of Hungarian noblemen in Constantinople.

According to Byzantine chronicles, missionaries met Hungarian tribes in the course of their wanderings throughout Central Europe and, in the middle of the 10th century, baptized a number of Hungarian noblemen in Constantinople.

Hungary’s first king, the fervent Saint Stephen (997-1037) received his crown from Pope Sylvester II. Crowned on Christmas Eve of the year 1000, Stephen eventually founded 10 Latin dioceses; two of them, Esztergom and Kalocsa, developed into metropolitan archdioceses. Although Byzantine eparchies were not established, monasteries following the Byzantine tradition flourished. The 11th-century coronation robe, for example, used for the kings of Hungary and now exhibited in the National Museum in Budapest, is the handiwork of Byzantine nuns living in the Hungarian realm at that time.

Hungary’s Byzantine Christians were almost completely destroyed during the Mongol invasion of 1241 to 1242. Byzantine Christian Vlachs and Ruthenians migrated to the border regions of the country (Subcarpathia, Transylvania and northern Hungary), replacing the native population.

Following the Great Schism of 1054, Hungary’s Byzantine Christians retained full communion with the Church of Constantinople, not with the Church of Rome. Attempts to heal the schism failed until the Council of Brest in 1596 achieved the union of Orthodox churches under the Polish-Lithuanian crown with the Church of Rome. Subsequent local councils succeeded in re-establishing full communion between the Orthodox churches and the Church of Rome in present-day Hungary, Romania, Slovakia and Ukraine.

Beginning in the late 18th century, Hungarian Greek Catholics began their quest to celebrate the Divine Liturgy in their native tongue – most did not understand the Church Slavonic used by the Greek Catholic Slavs, who also lived in the Hungarian domains of the Austrian Empire.

This quest was finally achieved two centuries later: on 19 November 1965, Bishop Miklós Dudás of Hajdúdorog celebrated the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom in Hungarian in Rome during Vatican II. The celebration of this liturgy is considered the ceremonial conclusion of the long struggle for a Hungarian liturgy.

In 1873 the Emperor Francis Joseph I founded a Hungarian Greek Catholic vicariate in Hajdúdorog. This vicariate was elevated to an eparchy with Pope Saint Pius X’s bull, Christifideles Graeci, on 8 June 1912. The Pope assigned 162 parishes into the new eparchy and established Old Greek as the language of the liturgy. He also appointed the Archbishop of Esztergom as the eparchial Metropolitan Archbishop.

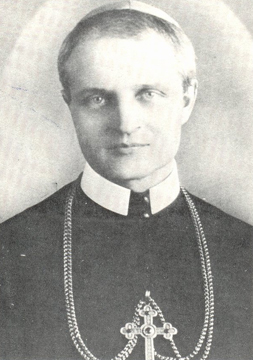

István Miklóssy became the first bishop of the new eparchy. Instead of settling in Hajdúdorog, however, he settled in the country town of Debrecen. On 23 February 1913 a mail bomb, sent by anti-Hungarian nationalists, exploded and killed the vicar, the secretary and the eparchy’s lawyer. Bishop Miklóssy was spared and moved to Nyíregyháza, another town in eastern Hungary. Since then this town has been the center of the Eparchy of Hajdúdorog.

After World War I, territories of the Hungarian state, including the Greek Catholic eparchies of Eperjes and Munkács, became a part of Czechoslovakia. Only 21 parishes remained in Hungary. In June 1924, Pope Pius XI founded an exarchate to include these parishes; the Apostolic Exarchate of Miskolc still exists today.

Bishop Miklós Dudás, O.S.B.M., succeeded Bishop Miklóssy in 1939. The 37-year-old Bishop Dudás began to develop the eparchy with great enthusiasm; he founded a People’s College in Hajdúdorog and in 1942 he opened a Greek Catholic Teachers Training Institute. He recruited Basilian religious to teach at the college. He founded a Greek Catholic students’ hostel in Nyíregyháza as well as 30 new parishes.

Bishop Miklós Dudás, O.S.B.M., succeeded Bishop Miklóssy in 1939. The 37-year-old Bishop Dudás began to develop the eparchy with great enthusiasm; he founded a People’s College in Hajdúdorog and in 1942 he opened a Greek Catholic Teachers Training Institute. He recruited Basilian religious to teach at the college. He founded a Greek Catholic students’ hostel in Nyíregyháza as well as 30 new parishes.

In 1950 Bishop Dudás established the Greek Catholic Theological Seminary within the walls of his own episcopal palace, thus encouraging the formation of seminarians in the Greek Catholic tradition.

Following World War II, a great number of Greek Catholics moved to the industrial regions of the country, thereby isolating themselves from their villages, families and distinct Greek Catholic traditions. At Bishop Dudás’ request, the Holy See temporarily extended the Bishop’s authority – heretofore confined to eastern Hungary – to all Greek Catholics living in the country. The Bishop’s successful reign ended with his death in 1972.

In 1975 Pope Paul VI appointed Father Imre Timkó as bishop, and selected Father Szilárd Keresztes as his auxiliary.

Bishop Timkó considered the renewal of the eparchy one of his most important tasks. Orientalium Ecclesiarum, decreed by Vatican II, invited the Eastern Catholic churches to return to their Eastern traditions. Accordingly, Bishop Timkó urged the study of Eastern theology, iconography and liturgy. He modernized both the eparchy center and the seminary with aid offered by West European Catholics and Greek Catholics living in the United States and Canada.

In 1980, Pope John Paul II extended the authority of the Bishop of Hajdúdorog to the entire territory of Hungary, with the exception of the exarchate. Bishop Timkó organized a general vicariate in Budapest for Greek Catholics living in the diaspora and appointed Bishop Szilárd Keresztes with its direction. Bishop Imre Timkó died unexpectedly in 1988.

After World War II, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland and Romania fell under the power of the Soviet Union. In a few years the Communists established atheist dictatorships in these countries, beginning in Ukraine in 1946. Churches were officially incorporated into the Orthodox Church. In 1948 the Greek Catholic Church was eliminated in Romania. The Greek Catholic Church in Czechoslovakia was also liquidated in 1950, but restored in 1968.

Luckily, the Greek Catholic Church in Hungary survived. More than 250,000 Greek Catholics, however, shared the fate of the nation’s 6.6 million Latin Catholics – terror and threats. In 1948, 3,148 church schools were nationalized in Hungary; among them were 134 Greek Catholic schools.

On Christmas Eve of that year conditions for the churches of Hungary worsened: József Cardinal Mindszenty, Archbishop of Esztergom, was taken from his palace and thrown into prison. The following year, religious life was prohibited in the country; 2,500 monks and 10,000 nuns were forced out of their monasteries and thrown into the streets. The state went a step further and established the State Office for Church Affairs (SOCA) in 1951, with the intention of obtaining total control and supervision of all churches in Hungary – Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox – by limiting religious life, winning over clergymen and laity and eliminating resistance. Youth programs were prohibited and religious activities were confined within church walls. Censorship was also introduced. All major construction work and the filling of higher posts had to be authorized by SOCA.

The year 1989 was a turning point for Hungary. The Communist autocracies in Eastern Europe had collapsed. Without a successor, the State Office for Church Affairs ceased to exist. Again people could freely exercise their faith. The Greek Catholic Church was legalized in Ukraine and in 1990 Pope John Paul II nominated Greek Catholic bishops in Romania.

Following the death of Bishop Timkó in 1988, Pope John Paul II named Bishop Szilárd Keresztes as his successor. Greek Catholic bishops and priests of the neighboring countries were received in Hungary with a fraternal welcome. The Eparchy of Hajdúdorog collected vestments, liturgical books and equipment for Greek Catholics in Subcarpathia and Romania. In 1990, for the first time in the history of the seminary at Nyíregyháza, 10 foreign seminarians enrolled.

The Greek Catholic Church in Hungary continued to flourish. In Hajdúdorog first a Greek Catholic elementary school and then a secondary school were established. The eparchy again published the Greek Catholic Review, which the Communists had suppressed.

A great event for the church in Hungary occurred when Pope John Paul II visited in 1991. The Pontiff celebrated the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom in Máriapócs, the historic place of pilgrimage for Hungarian Greek Catholics.

Another important step occurred in 1992, when an agreement was signed with the Teachers Training College in Nyíregyháza; the training of laity as catechists could now begin. A corresponding department in the seminary was also established. The seminary, supported in part by CNEWA, has undergone great development; academic work is directed by teachers who studied abroad, mainly in Rome. Consequently, the theological faculty was qualified as an affiliate of the Pontifical Oriental Institute in Rome in 1995. The seminary library continues to grow each year and the construction of a new building is in the works. Thanks to its central location, Bishop Szilárd Keresztes has expressed a desire to involve the seminary in the spiritual and intellectual revival of the Eastern Catholic churches of central and Eastern Europe.

True to his word, Bishop Keresztes acted as host in 1997 for the first meeting of European Eastern Catholic Bishops. Led by Achille Cardinal Silvestrini, Prefect of the Holy See’s Congregation for the Eastern Churches, 40 Greek Catholic bishops and 66 leading officials from 20 countries participated in the meeting. In 1998, the principals of the Eastern Catholic seminaries in Europe attended a refresher course in Nyíregyháza.

True to his word, Bishop Keresztes acted as host in 1997 for the first meeting of European Eastern Catholic Bishops. Led by Achille Cardinal Silvestrini, Prefect of the Holy See’s Congregation for the Eastern Churches, 40 Greek Catholic bishops and 66 leading officials from 20 countries participated in the meeting. In 1998, the principals of the Eastern Catholic seminaries in Europe attended a refresher course in Nyíregyháza.

There has been further advancement in the Greek Catholic Church in Hungary. The number of clergymen, for example, has increased in the last 50 years: While in 1945 the number of Greek Catholic priests was as low as 202, it has grown steadily over the years to 233. More than 90 percent of the Greek Catholic clergymen living in Hungary have families, several with four or more children. These clergymen and their wives participate monthly in a recollection program and attend an annual retreat in Máriapócs.

The number of seminarians has also increased. In addition, Hungarian seminarians from neighboring countries opt to study in Nyíregyháza. More than 100 students attend regular and correspondence courses for religious teachers. The number of monks and nuns, however, has decreased since 1950.

The number of parishes in Hungary has increased as well, from 126 in 1945 to 167 today. During the last decade alone, 25 Greek Catholic churches have been erected.

The core of this church’s spiritual life is the Divine Liturgy and its Greek Catholic rites and traditions. Patronal feasts and the spiritual exercises conducted during Lent represent major events in the parishes. Parish-organized pilgrimages, mainly to Máriapócs, on 15 August (the Feast of the Dormition) and on 8 September (the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary), draw tens of thousands of people who pray and sing together in one voice.

On viewing its turbulent history, it is clear that the Hungarian Greek Catholic Church has experienced great development. We trust that God will continue to help us in fostering our liturgy and spirituality, giving witness to the unity of the Catholic Church for future generations.

Dr. Janka György is head of the Department of Church History at the Greek Catholic Theological Institute at Nyíregyháza.

Hungarians Gather to Honor Mary

A rustic icon draws tens of thousands of pilgrims

by Jacqueline Ruyak

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

As we made the turn for Máriapócs, Father Tamás Horváth pointed out two white-haired women walking along the road.“Pilgrims,” he said.“They’re probably on their way from the train station.” It is less than two miles from the station to Máriapócs, a little Greek Catholic village (population, 2,800) that is Hungary’s most beloved pilgrimage site.

“Walking is a kind of sacrifice offered to Mary,” he added.

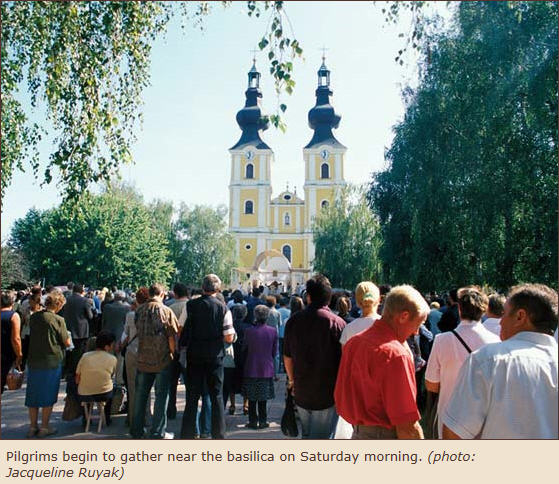

It was the second Saturday of September in northeastern Hungary and the weather was perfect. Apples, pears and plums were in season, grapes were on the vine and roses, marigolds and herbs still scented the air. On the following day, Bishop Szilárd Keresztes, Greek Catholic Bishop of Hajdúdorog, would celebrate an open-air liturgy in Máriapiócs to commemorate one of the principal feasts of the Virgin Mary, her Nativity.

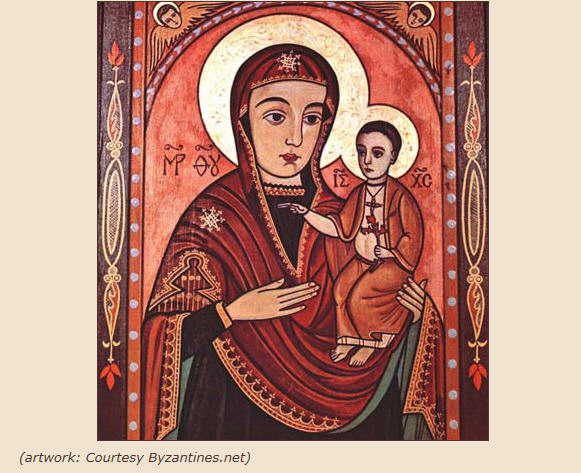

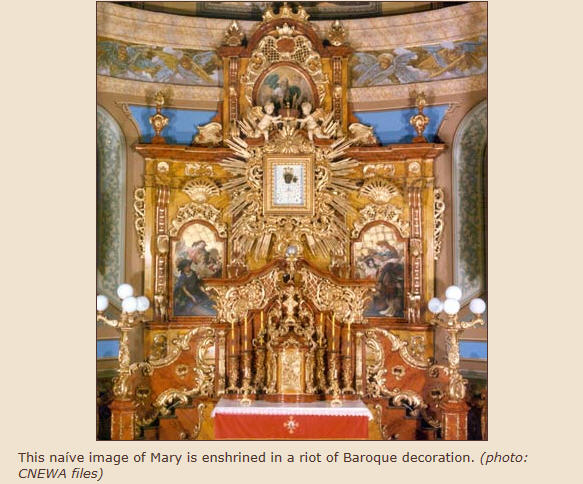

For more than three centuries, Máriapócs (formerly the village of Pócs) has been known for its weeping icon of the Virgin Mary (opposite). Commissioned in 1676 by a local man who had escaped imprisonment by the Turks, the icon first wept in 1696. Cures and miracles were soon attributed to it. In 1697, by order of the Hapsburg emperor of Austria, the icon was taken to St. Stephen Cathedral in Vienna and replaced with a copy. The original icon, which remains in Vienna, never again shed tears, but the copy has purportedly wept twice, in 1715 and 1905. Both moments marked periods of hardship in Hungarian history. The first instance marked the Hapsburg army’s defeat of an independence movement led by the Catholic revolutionary Ferenc Rákóczi. And in 1905, Hungary was impoverished, with an estimated 3 million beggars roaming the countryside.

Since 1696, millions have paid tribute to this simple image of Mary. The wooden church that originally housed the icon was too small to accommodate the many pilgrims who flocked to the village and, in 1756, a Baroque church was built to replace it. In 1946, Pope Pius XII raised this rural church to the status of a minor basilica. After the Communists came to power in Hungary in 1948, religious processions came under state scrutiny. At times, pilgrimages were forbidden and state agencies kept track of disobeying citizens. More often, pilgrimages were discouraged and subject to state-sanctioned harassment. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989, pilgrimages resumed in earnest.

Every Sunday from spring to autumn there is a feast. The shrine’s two main pilgrimage days fall in late summer: 15 August, the feast of the Dormition, or the falling asleep of the Virgin Mary, and 8 September, the Nativity of the Virgin. Both are celebrated on the Sunday closest to the actual feast day. Going to Máriapócs on foot has long been a way of offering a sacrifice. Ílona Konyári, 81, from the Greek Catholic village of Nyírascád, about 22 miles away, recalled such pilgrimages. “We went to Máriapócs at least once a year, usually three times, on foot. There were two or three hundred of us, with the church banners and village crest. The baggage was carried in a cart but we walked, singing hymns as we went. While we walked, the priest heard confessions.

Whenever we came to a cross along the way, we’d stop to pray and sing. When we came to a village, we prayed at the church there, and the church rang its bells. We left around nine in the morning and arrived that night. We looked for a place to stay, then took part in the feast day ceremonies and liturgy. And we kept on going even under Communism.” About 30 years ago, pilgrims started using buses, however, because Communists along the way had taken to taunting, spitting, throwing stones or otherwise harassing those on foot. Seven years ago, the bishop built a snug pilgrimage house, open year round, where pilgrims may stay for a nominal charge. Long ago, pilgrims stayed in the stables of local homes. Villagers took their animals out so that pilgrims could stay; they were repaid with gifts of fruit or other foods. Some homes still put pilgrims up, but as paying guests. Most pilgrims now come to Máriapócs on the morning of the feast day itself.

Father Horváth and I reached the pilgrimage house, where I would stay, in time for a late lunch in the cafeteria. The homemade vegetable soup, of carrots, parsnips and little dumplings, made me wonder if it was a fast day. That notion was dispelled by the csikóstokány, pork ragout in a flavored sour cream sauce served over macaroni, which followed. Because the Nativity of the Virgin is a joyous occasion, there is no fast. For the Dormition, fasting begins after 29 June, the feast of Sts. Peter and Paul, and continues on designated days until 15 August. “Pilgrims usually bring their own food,” Father Horváth said.“They take some of it back with them, because food that has been to Máriapócs is a treat for the people at home. They call it madárlátta, food seen by the birds.” Other traditional treats are mézeskalács, honey cakes, which were being sold at stands off the main square. Pilgrims to Máriapócs first greet the icon, which is installed high above a side altar, to the left of the iconostasis.

Afterward, some pilgrims go to confession. Others continue up a short flight of stairs, where they kiss a glassed miniature of the icon, exiting down the opposite side. When I went to the church that afternoon, a wedding was in progress. Both bride and groom were Romany, commonly known as Gypsies. Of Hungary’s total population of some 10 million, about 600,000 are Romany, who usually claim the religion of their resident community. In northeastern Hungary, many are Greek Catholic.

Throughout the liturgy, pilgrims shuffled up and down the stairs behind the altar. Once the newlyweds departed, believers surged to the altar to pray, sing and light votive candles. Some offered flowers, others sought blessings. A Romany woman, four children in tow, kissed the altar from end to end. A young man prayed, then took a photo of the icon with his cell phone. In a book set out for that purpose, a middle-aged man laboriously wrote a message of thanksgiving for being able to greet the icon with his family. Several years ago Bishop Szilárd built about 30 confessionals in the back of the church. On feast days, priests hear confessions for hours at a time, but the confessionals are still too few and pilgrims line up on the grass behind the church.

“Pilgrimage means getting greater grace,” said Father Horváth,“and being able to live with this grace for another year. People come here asking for grace and receiving grace, asking God and the Mother of God to help them prepare for the next year.” For Demeter Kosztin, a 75-year-old widower who also lives in Nyírascád, Máriapócs is a place to think of his family.“I offer prayers to Mary and to Christ for my children and grandchildren and for peace and tranquillity in the family. “I also ask the Mother of God that I may live to come again next year.” Eva Kocsis, in her 20’s, was at the church with one of her six sisters.“Máriapócs is the center of Greek Catholic life,” said Ms. Kocsis, editor of a Greek Catholic magazine. “When I have problems, I come and tell Mary. Like small children love their mother, we love the Mother of God.”

To Greek Catholics, explained Father Horváth,“Mary is a real, not mystical, figure. She was the Mother of God and, like us, a human being. In a family, when people want something, they go first to the mother and ask her. For us, the head of the family is God, who we know loves us, but it is easier to ask things of his mother.” By seven o’clock, the evening had turned dark and distinctly cool. A hundred or so pilgrims walked to the cemetery, about 10 minutes away, for a traditional ceremony for the dead. Priests and seminarians led the service, by flashlight, at the main cross of the cemetery. The illuminated towers of the church shone behind us; the Big Dipper hung over the horizon. A huge old tree loomed out of the darkness down the path where we stood, and somewhere in the night dogs were barking.

There suddenly came the insistent beat of a rock band, music from an amusement park on the other side of town. Once a market that catered to pilgrims, it had morphed into an amusement park. Under the Communist regime, the park was set up across from the cemetery to disrupt ceremonies there, but in the 1990’s it was finally moved to an open field across town. “When I came to Máriapócs as a child it was scary,” said Father Horváth on the way back. “There were so many people here, and they jammed together. You never knew what the Communists would do, so people stuck together, to be as close as possible.” Back again at the church, the murmuring ebb and flow of worshipers continued into the night. Priests led the pilgrims in singing services from nine to almost midnight.

Between services, a man dressed in grubby vestment-like garb stepped forward from the congregation and started singing, perhaps with more fervor than skill. He was joined by a raucous middle-aged Romany man, one of many pilgrims I recognized as having been there since afternoon. At midnight, Father Horváth led everyone outside and in a procession around the church. Father Horváth, who had been ordained a priest barely a month earlier, read aloud the story of the Resurrection from the Gospels and blessed each of the four sides of the church. He later explained that in the past the procession went around Máriapócs, “bringing grace throughout the village.” High above the ochre and white church towers, stars glittered in the blue-black sky. The crowd, which in the church had taken on a slightly giddy air, became quiet and intent as the procession made its way around the shrine.

When I woke just past five on Sunday morning and looked out the window, I was astounded to see waves of people streaming along the paths to the church. By seven, the waves had become a flood. Priests led their parishioners, some bearing flowers, banners, crosses, small statues, paintings or signs, into the church. Other pilgrims, in coiled lines two or three deep, waited alongside the church to kiss the icon. Around eight, as if on cue, those who had worshiped took out bread or sandwiches from home – breakfast. At a holy water font near the rear gate, Romany women rinsed their faces and then scrubbed their children’s faces. The lines for confession grew longer. Thousands of believers of all ages thronged the grassy square in front of the church walls to hear the bishop celebrate the Divine Liturgy at 10. During the liturgy, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of its last weeping, he announced the icon would travel around the country. This was a first in its long history. “We love this icon, not the material icon but what it represents,” said Father Horváth.“We are happy and proud to have such a protector, and now each village and town in Hungary will be able to feel that it is a guest.”

In recent years, I was told, the number of pilgrims had fallen off, but the official police estimate of the day’s crowd was 60,000. By 10 that morning there were so many people inside that the gates to the church had to be closed and the patient pilgrims made to wait outside for their turn to enter. During Communion, Bishop Szilárd sent many concelebrating priests into the churchyard to give the Eucharist to the pilgrims. It went on long after the liturgy had ended. And at three that afternoon, pilgrims were still milling about the church, asking Mary for her intercession on the day of her birth.

The Shrine of Máriapócs

Máriapócs, Hungary

The Weeping Icon of Marijapovch (Mariapocs) has been revered by Carpatho-Rusyn and Hungarian Greek Catholics for centuries. The Village of Povch (former Szabolcs County) is located in the northeastern section of Hungary. A Basilian Fathers Monastery constructed a beautiful church here. Stefan (Istvan) Papp, brother of the priest of the Povch town church was commissioned to paint an icon of the Mother of God for the iconostasis. The name of this village is found in early writings of the thirteenth century as the estate of the Bathory family. Later this estate was transferred to the Karolyi family.

The Weeping Icon of Marijapovch (Mariapocs) has been revered by Carpatho-Rusyn and Hungarian Greek Catholics for centuries. The Village of Povch (former Szabolcs County) is located in the northeastern section of Hungary. A Basilian Fathers Monastery constructed a beautiful church here. Stefan (Istvan) Papp, brother of the priest of the Povch town church was commissioned to paint an icon of the Mother of God for the iconostasis. The name of this village is found in early writings of the thirteenth century as the estate of the Bathory family. Later this estate was transferred to the Karolyi family.

Stefan Papp painted the Virgin Mary on wood holding the infant Jesus with a tulip with three petals in his hand. Lorincz Hurta paid for this icon and donated it to the church. The first weeping of the icon occurred in the wooden Greek Catholic Church in Povch on November 14, 1696. During the mass, those who were in the church noticed teardrops running from both eyes of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The same miracle took place each year from December 8 to 19. From the first weeping of the icon, the village of Povch was called Marijapovch (in Hungarian Mariapocs.) Mariapocs is the most famous and most visited place of worship in Hungary. It is the spiritual center of the Greek Catholic faithful. Today, it is estimated that 600,000 to 800,000 pilgrims visit this Shrine each year. News of these events travelled quickly and soon reached the Imperial capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Emperor and Empress of Austria-Hungary requested the Icon be brought to Vienna as both had a special devotion to the Virgin Mary. The icon was carried in procession throughout Vienna. It arrived on July 4, 1679. The Emperor asked the icon be placed in the Stephansdom of Vienna. It is still found to this day on the altar in the southern aisle where it is still venerated. The residents of Pocs were deeply saddened by the loss of their beloved icon. Ference Rakoczi II even addressed a letter to the Emperor asking for its return. Copies were made with one being sent to Mariapocs. After the copy was delivered to the church, Mihaly Papp, the priest of the Greek Catholic church in Pocs, was celebrating mass on August 1, 1717 when the Cantor noticed the icon was weeping. This event was witnessed by hundreds of people. During this time the Bishop of Eger, Gabor Antal Erdody, had the icon officially examined. His investigation concluded the weeping was authentic. Later, the icon again began to weep. During the mass in Mariapocs the third and last weeping began on December 3, 1905. Father Kelemen P. Gavris was leading a pilgrimage at this time. The weeping was examined by both church and secular committees and they also verified weeping indeed was taking place. One of the silk cloths which captured the tears can still be seen under the icon.

At this point hundreds of people were coming from long distances to worship in front of the icon. They came from all parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire such as present day Slovakia, Ukraine, Southern Poland and Czech Republic. However, the church was small and could not accommodate a large congregation. It was decided to build a larger church. The construction was begun by the Superior of the Basilicans, Father Gennadius Gyorgy Bizanczy. It was continued under the tenure of Bishop Mihaly Oslavszky who also began to construct the present monastery building. The actual church of Saint Michael was constructed between 1731 to 1756. Two towers were built with domes, these were completed in 1856. The iconostasis was built during the years 1785 to 1788 and was replaced by a new iconostasis in 1896. The exterior of the church was renovated from 1893 to 1896. Later much needed repairs were made in 1991. Below the church in the crypt a number of Greek Catholic Bishops, priests and those who supported the shrine are interred. A devotional altar was made in the 18th century and an altar to Saint Basil the Great was constructed in the 19th century. During the war years, artistic murals were added by Jozsef Boksay and Ammanuel Potrasovszki. Pope Pius XII awarded the title “basilica minor” to the church of Mariapocs.

The greatest honor bestowed on this historical and beloved Greek Catholic shrine came on August 18, 1991. Pope John II visited Hungary and celebrated a Byzantine Rite mass in front of the holy icon. Thousands of pilgrims attended this historic event. Throughout its history there have been many miracles attributed to this icon. Many people reported healings; others were converted to the faith. One recorded miracle was of a soldier who asked to be baptized immediately after gazing upon the icon. It is interesting to note that not only is this a pilgrimage place for Greek Catholics, numerous Roman Catholics and even those of the Protestant faith make pilgrimages here.

The greatest honor bestowed on this historical and beloved Greek Catholic shrine came on August 18, 1991. Pope John II visited Hungary and celebrated a Byzantine Rite mass in front of the holy icon. Thousands of pilgrims attended this historic event. Throughout its history there have been many miracles attributed to this icon. Many people reported healings; others were converted to the faith. One recorded miracle was of a soldier who asked to be baptized immediately after gazing upon the icon. It is interesting to note that not only is this a pilgrimage place for Greek Catholics, numerous Roman Catholics and even those of the Protestant faith make pilgrimages here.

The Hungarian Catholic Episcopacy announced that December 1, 2005 would designate Máriapócs as a National Place of Worship. This announcement was made by Cardinal Peter Erdo and on December 3, 2005, he dedicated Hungarian and the Greek Catholic church to the protection of the weeping Blessed Virgin of Máriapócs.

Prayer to Our Lady of Mariapoch

O most Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of mercy, adorned with miracles, whose icon shed tears at the place of your mercy in Mariapoch, we who honor you, humbly beseech your motherly care. Save our country from all its enemies; protect the Church; and join all in one faith that, at last, the words of Christ may be fulfilled: “There shall be one fold and one shepherd.” Do not deny us your intercession; and obtain for us peaceful times, health for our bodies and peace for our souls. Obtain grace for us that our last hour finds us in the Christian faith and in a state of grace so that we be enabled to gain eternal salvation. Amen.

Our Town (Roma Greek Catholics)

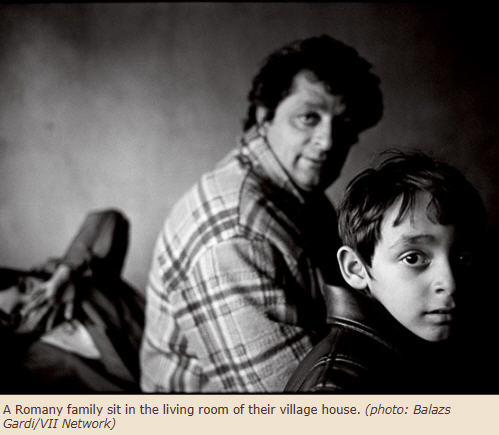

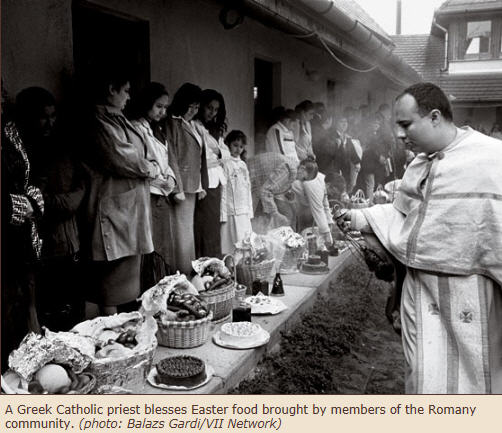

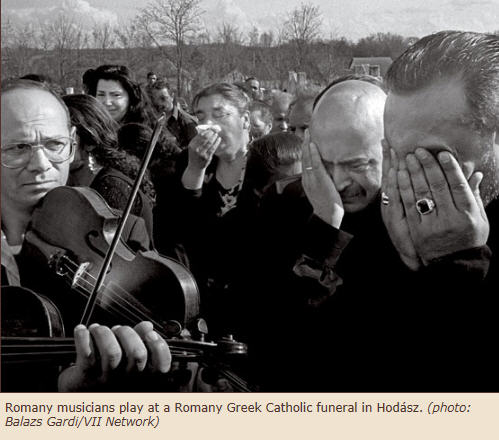

by Jacqueline Ruyak with photographs by Balazs Gardi/VII Network

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

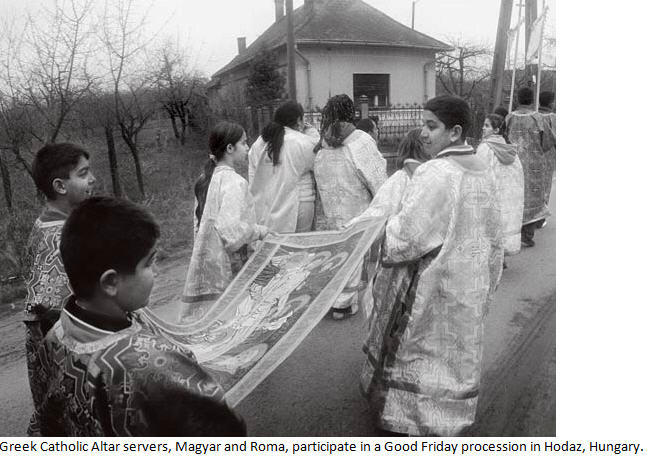

Hodász is different,” said Father Tibor Egri, a Greek Catholic priest in this village of some 3,500 people in northeastern Hungary. What makes Hodász exceptional is not its assorted parishes – Greek and Roman Catholic and Evangelical Protestant – or its mixed population of ethnic Hungarians and Roma, commonly called Gypsies. Rather, it is how these distinct groups have forged a cohesive community. “People here get along easily,” Father Egri continued. “Many Hungarians associate the Roma with criminal activities. And the media reinforce the stereotypes and feed the prejudices. “Roma here,” he added, “tend to be more ’Hungarian,’ which makes it easier.” With up to 800,000 Roma now living in the country – between 5 and 10 percent of the overall population – Hungary typifies the Romany experience as a disenfranchised minority and yet offers hope for greater Romany social and political inclusion.

Hodász is different,” said Father Tibor Egri, a Greek Catholic priest in this village of some 3,500 people in northeastern Hungary. What makes Hodász exceptional is not its assorted parishes – Greek and Roman Catholic and Evangelical Protestant – or its mixed population of ethnic Hungarians and Roma, commonly called Gypsies. Rather, it is how these distinct groups have forged a cohesive community. “People here get along easily,” Father Egri continued. “Many Hungarians associate the Roma with criminal activities. And the media reinforce the stereotypes and feed the prejudices. “Roma here,” he added, “tend to be more ’Hungarian,’ which makes it easier.” With up to 800,000 Roma now living in the country – between 5 and 10 percent of the overall population – Hungary typifies the Romany experience as a disenfranchised minority and yet offers hope for greater Romany social and political inclusion.

For generations, Hungary’s Roma have endured institutionalized discrimination in education, housing and employment. Societal prejudices run deep as well; hate crimes against Roma remain relatively common. But this central European nation’s Roma enjoy better legal protection and greater representation in government than most Romany populations in other European nations of the former Communist bloc. Roma, who now make up nearly half the village population, have lived in Hodász at least since 1820, when local authorities recorded the first Romany baptism. As in the rest of Europe, Roma now constitute the fastest-growing ethnic group in Hungary; one out of every five or six newborns is Roma. In Hodász, however, all villagers tend to have small families, which usually include no more than two children.

“It’s a kind of acculturation,” said Father Egri, who has served for four years as curate at the Greek Catholic Church of the Ascension, the spiritual center of the village’s estimated 400 Greek Catholic Roma. But Ascension, one of the 145 parishes of the Eparchy of Hajdúdorog, has assumed many of the cultural traditions typically associated with the Roma while maintaining its Greek Catholic ethos. Music and dance play a central role in Romany culture. At Ascension, Romany singers, guitarists and other instrumentalists have replaced traditional Greek Catholic plainchant. “Maybe it’s in our genes,” suggested cantor Sandor Lakatos. “We recognize each other by our way of singing and dancing.”

The Romany Greek Catholic parish also celebrates the liturgies in Lovari – the local Romany dialect. A key part of Romany identity, most Roma in Hodász speak it as a first language. “We speak Romany first of all, so we think in a Romany way even when speaking Hungarian,” said Mr. Lakatos. A vital force in the cultural life of Hodász’s Roma, the Church of the Ascension reaches out to the entire village community through its St. Elijah Shelter and Day Care Center. Run on a shoestring budget, the facility manages to offer a host of essential social services at a time when state-run programs are being cut. More than 50 people – Roma and ethnic Hungarians – live at the shelter, 22 of whom are homeless pensioners and a score of women who, with their children, have sought refuge there from their violent homes. St. Elijah’s also provides daily meals – breakfast, lunch and dinner – to an additional 50 villagers or more.

The Romany Greek Catholic parish also celebrates the liturgies in Lovari – the local Romany dialect. A key part of Romany identity, most Roma in Hodász speak it as a first language. “We speak Romany first of all, so we think in a Romany way even when speaking Hungarian,” said Mr. Lakatos. A vital force in the cultural life of Hodász’s Roma, the Church of the Ascension reaches out to the entire village community through its St. Elijah Shelter and Day Care Center. Run on a shoestring budget, the facility manages to offer a host of essential social services at a time when state-run programs are being cut. More than 50 people – Roma and ethnic Hungarians – live at the shelter, 22 of whom are homeless pensioners and a score of women who, with their children, have sought refuge there from their violent homes. St. Elijah’s also provides daily meals – breakfast, lunch and dinner – to an additional 50 villagers or more.

In addition to its crisis-intervention programs, St. Elijah’s staff of 30, most of whom are Romany women, cares for children of working parents and provides job training and employment counseling. Father Gábor Gelsei, pastor of Ascension for the past 14 years, oversaw the development and construction of the shelter and day care facility seven years ago. He financed the center largely through grants from a Dutch foundation. In 2001, Father Gelsei turned over the facility’s day-to-day management to the church cantor and Romany community leader, Sandor Lakatos. Mr. Lakatos has lived in Hodász his entire life. Though he spent 10 years as a construction worker in Budapest, as with many migrant workers from Hungary’s northeast, he returned home most weekends. When, in 1990, Mr. Lakatos resettled in Hodász, he worked for several years as an agricultural day laborer and became active in village politics. A former member of the village council, he now occupies a seat on Hodász’s Romany council.

According to the cantor, he first experienced discrimination while working in Budapest. But he says he has never felt discrimination in Hodász. “I think it’s because we all share the same faith in Jesus Christ. The priests who came to this village were looking for people, regardless of their skin color. When they found them, it was the start of a community. That was a great thing.” While grateful for the encouragement his deeply religious grandparents gave him as a child, the 65-year-old fondly remembers being inspired to serve the church by Father Miklos Soja, a charismatic priest who worked in the village in the 1950’s and 1960’s. Before Father Soja, priests only visited the village’s Roma when called upon for baptisms or weddings. “He was the first to work among the Roma here,” said Mr. Lakatos. “He lived in the non-Roma parish, but he learned Lovari, the Romany dialect spoken here, visited all the houses and became accepted. He deepened people’s faith and instilled a strong sense of morals and ethics. Because of him, even people in their 40’s and 50’s asked to be baptized and brought their children. In a sense, he brought the Roma Christian community here into being.

“When people called him ’father’ in Lovari,” he continued, “they used a very intimate meaning of the word, as if he were an actual father, not a priest.” Father Soja motivated his Romany parishioners to build the first Romany Greek Catholic church, which was replaced 12 years ago by the current structure. “Everyone worked together voluntarily,” recalled Mr. Lakatos. “I think that gave my generation a solid sense of community that young people now just don’t have. We had a church, a place to call home. It was our home, so we worked for it, did things for it. This here is not just a religious center, but also a place where we can learn how to manage daily life, how to use forks and spoons or computers and the Internet. If you are somewhere that is home and you feel that it is yours, you always feel safe.” That said, Hodász’s charismatic Romany cantor is frank, if not bleak, about his village’s future. “For young people, the only chance for a better life is to study, get a profession or trade and move away. For older people, there is no solution. We need capital to start something here.”

Unemployment, a major problem in Hungary, is especially acute in the nation’s underdeveloped northeast. By some estimates, nearly 80 percent of the village’s Roma and up to 25 percent of its ethnic Hungarians are unemployed. There are almost no jobs in the village. Young people often leave town to attend university or to seek better career opportunities. Most never return, except for the occasional family get-together. Whereas most ethnic Hungarian villagers work within commuting distance, Roma generally split their lives between Hodász and the distant capital, Budapest, where they can still find unskilled jobs. Under communism, Roma were assured work, albeit low paying. But since the dismantling of the nation’s state-controlled economy – which followed the collapse of Hungary’s Communist government in 1989 – many of these jobs, and the security they offered, have disappeared.